| HOME | About Barnaby | Books | Gallery | Reviews | Articles | Talks | Reading List | Links | Contact Info |

|

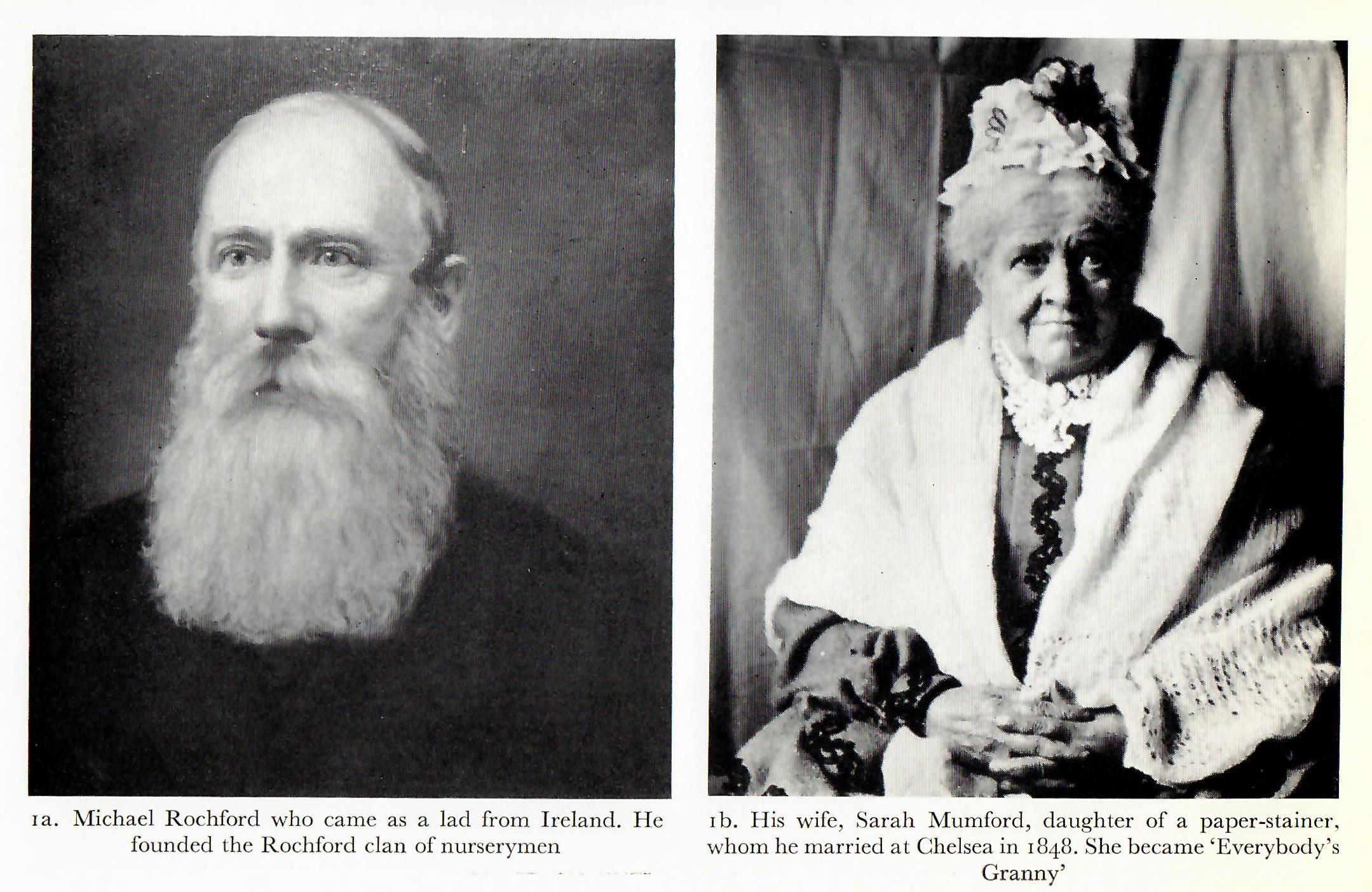

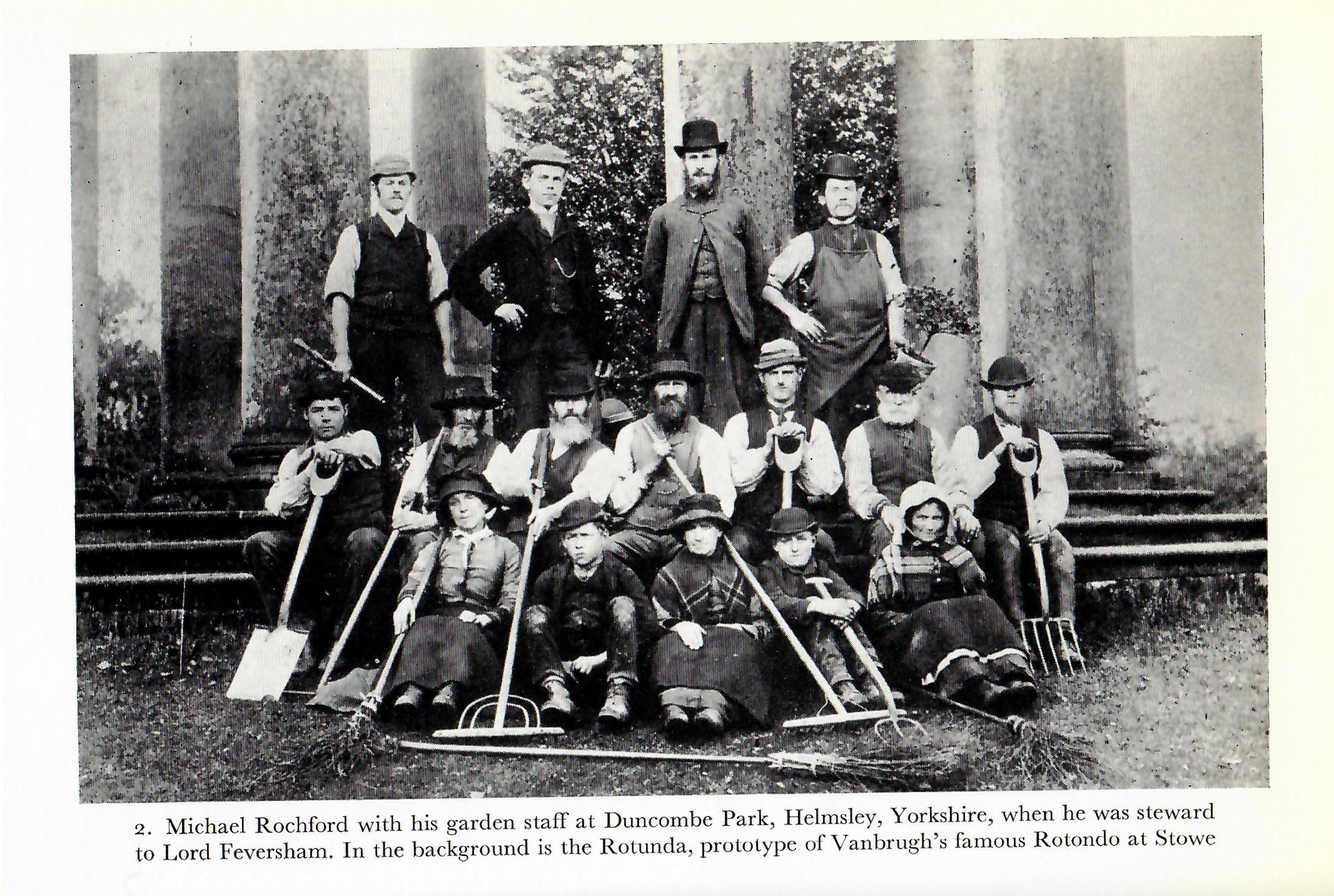

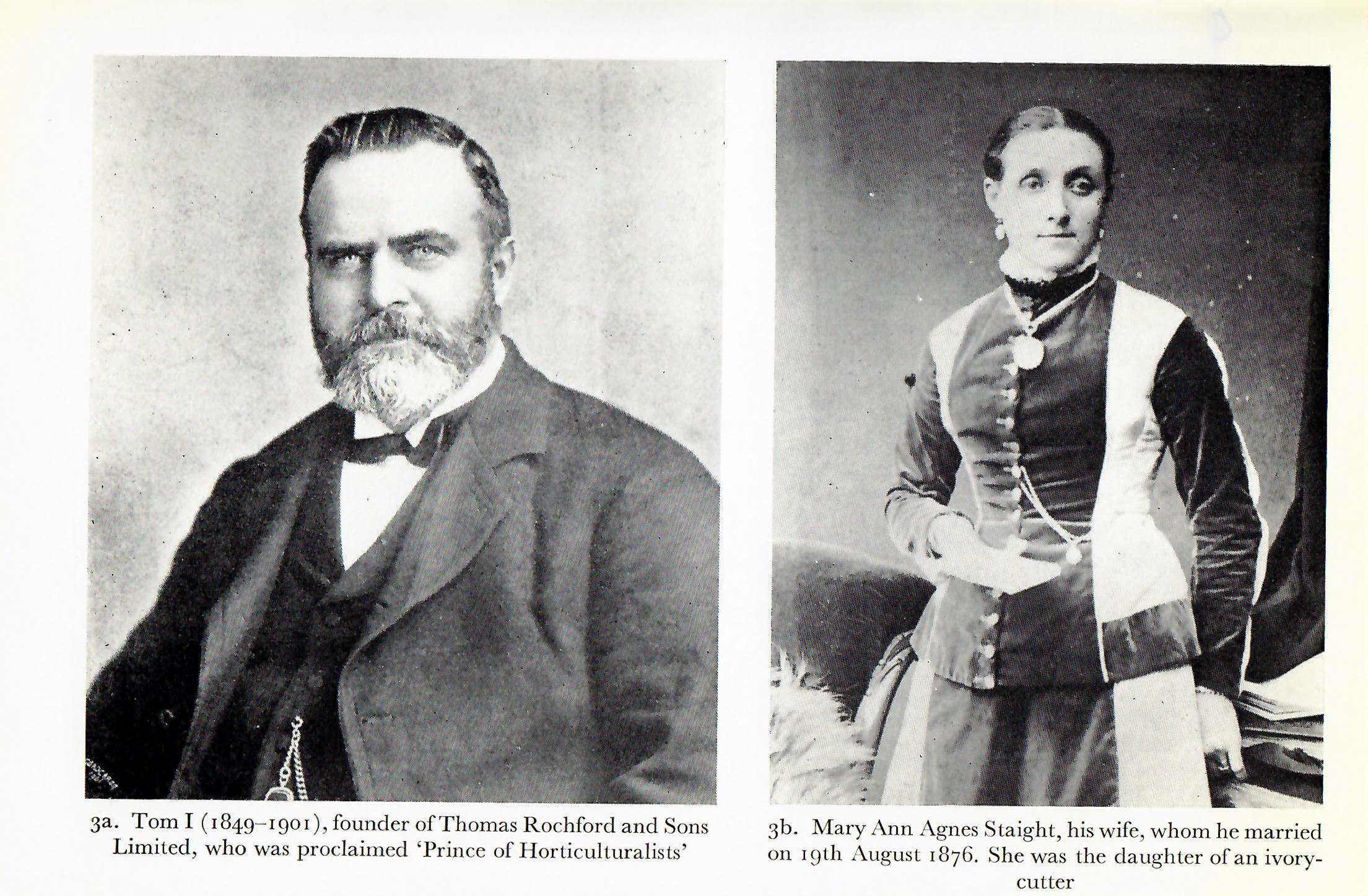

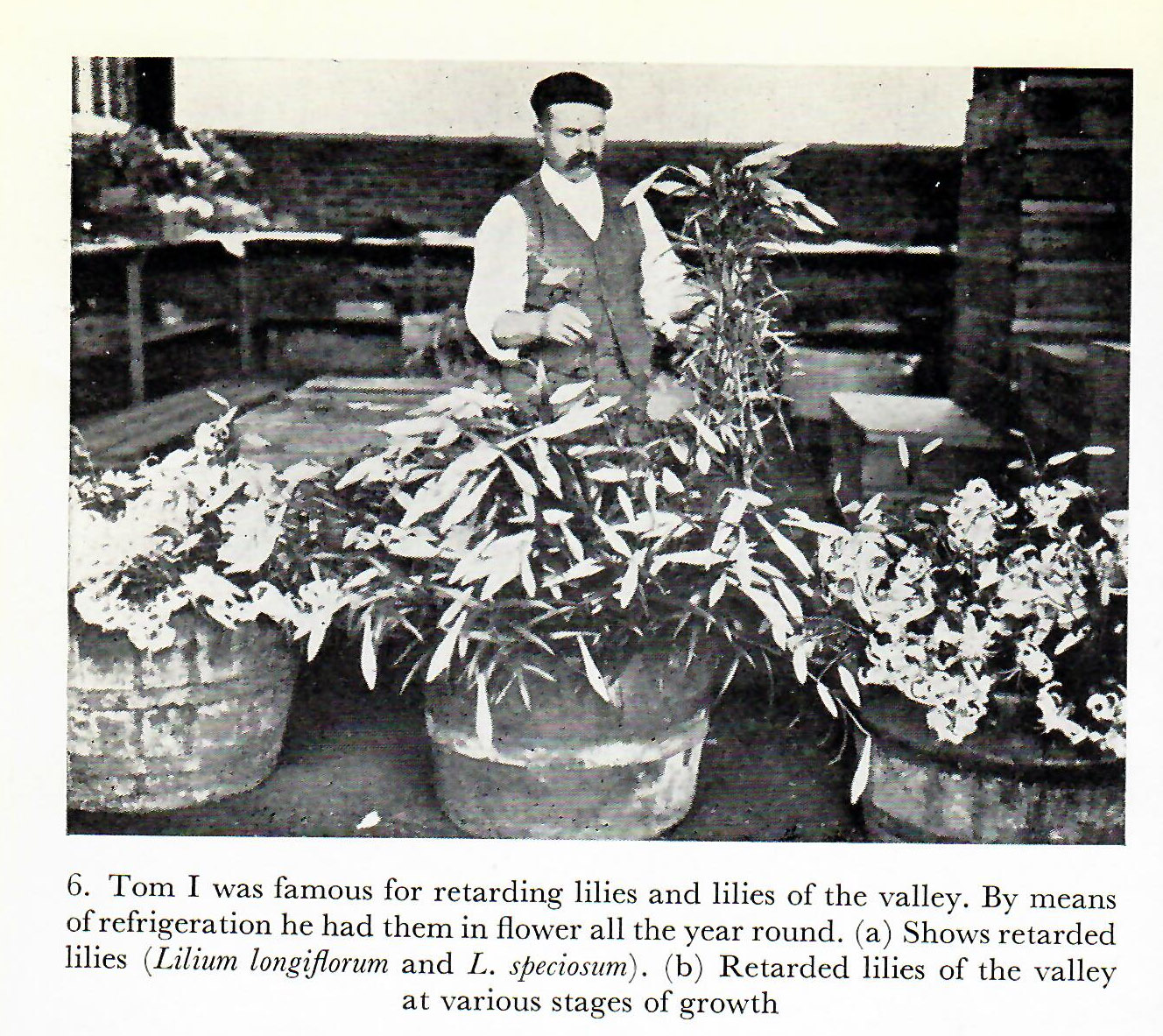

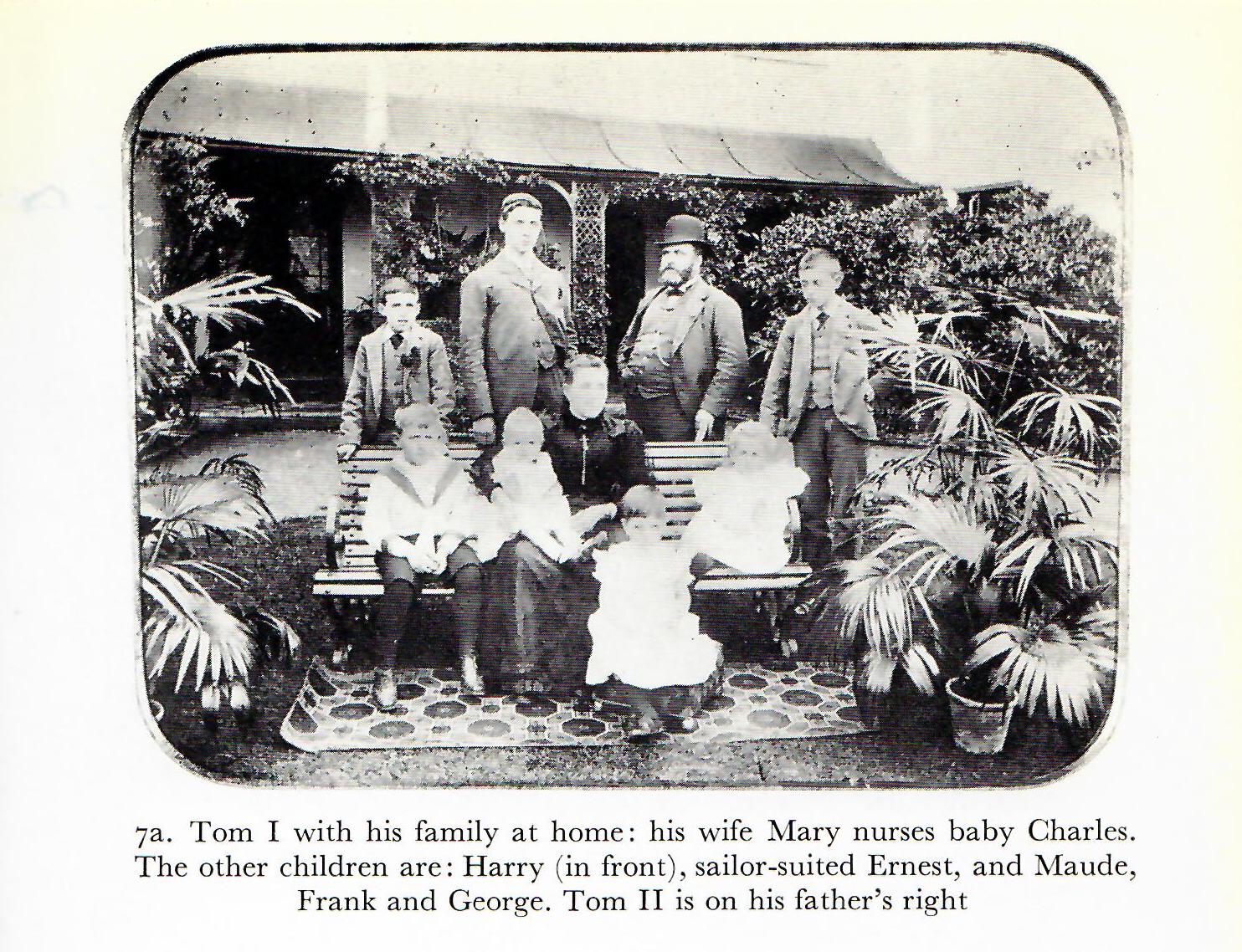

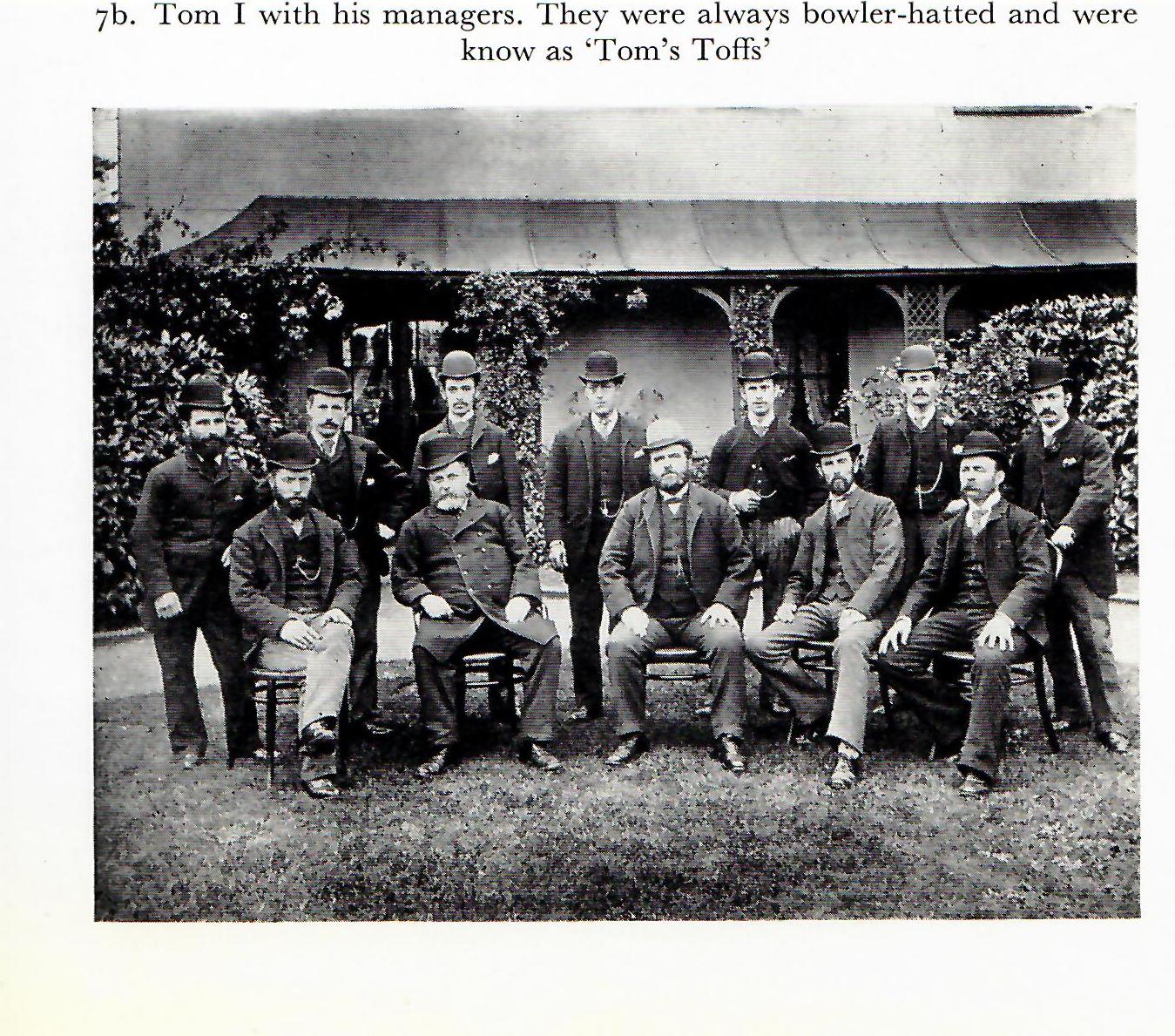

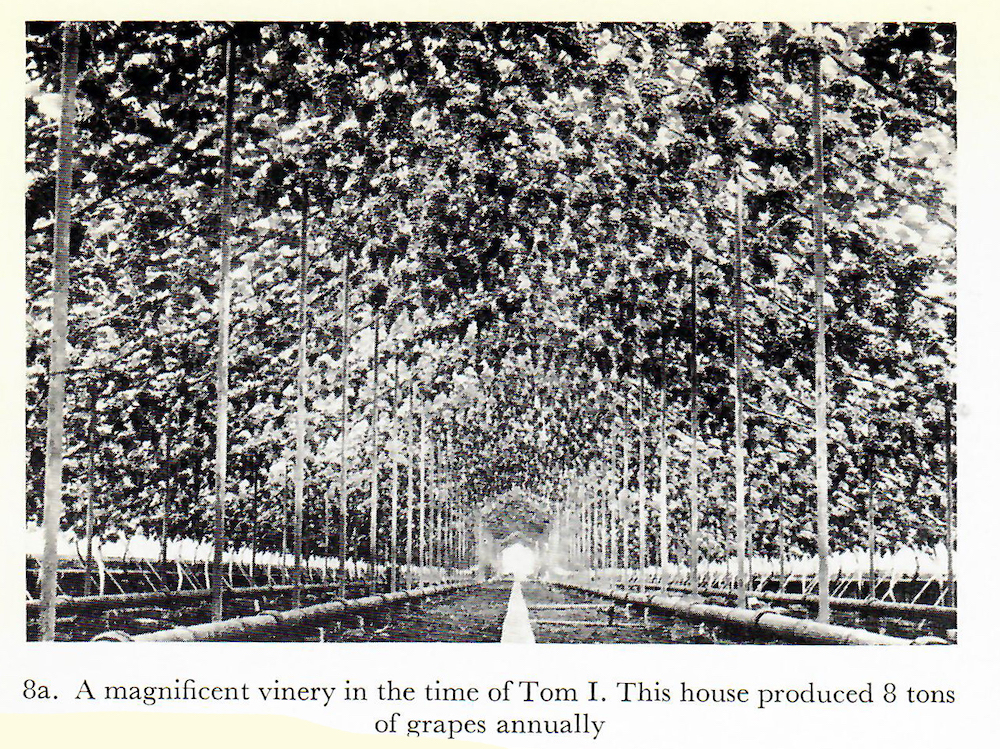

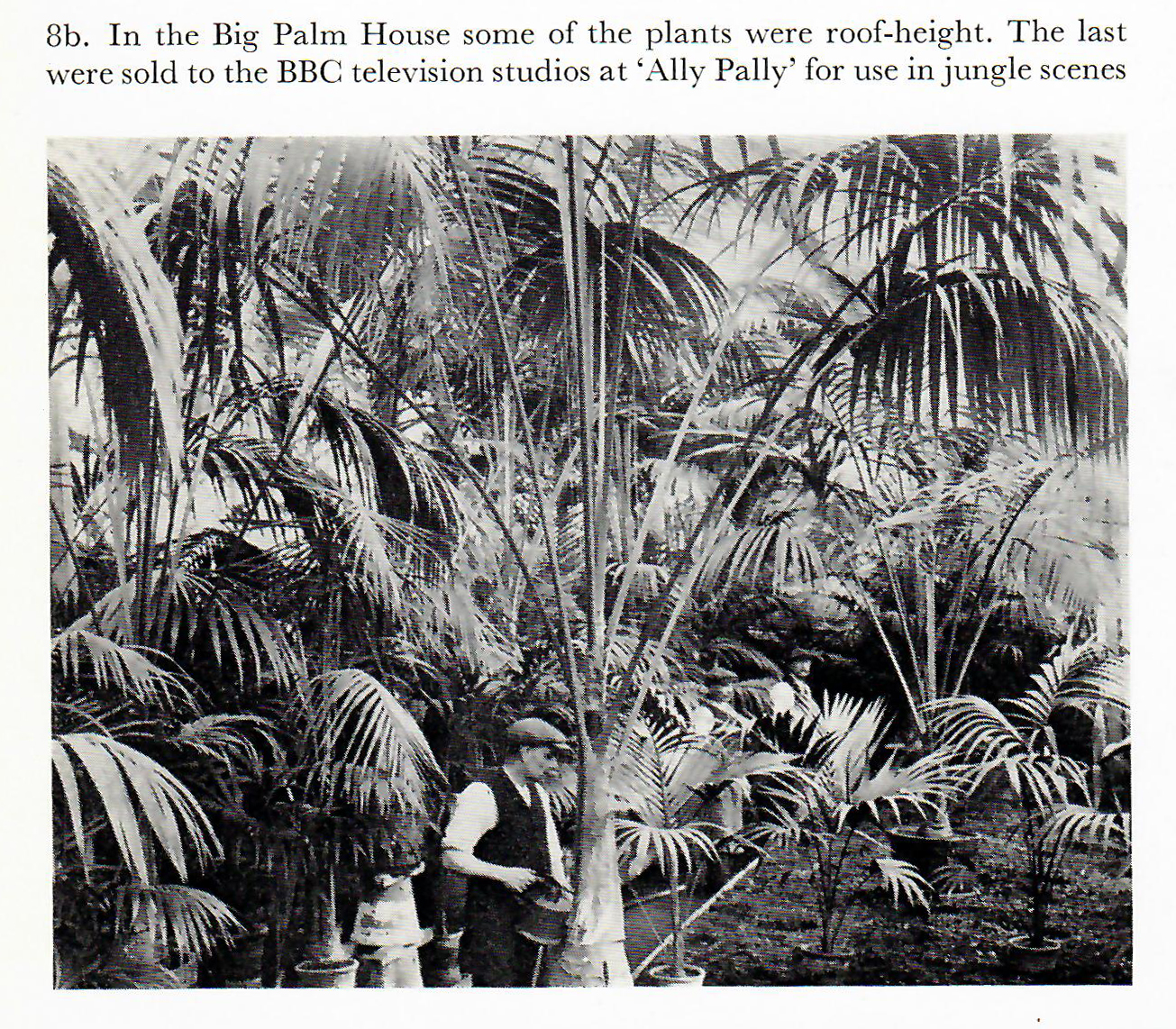

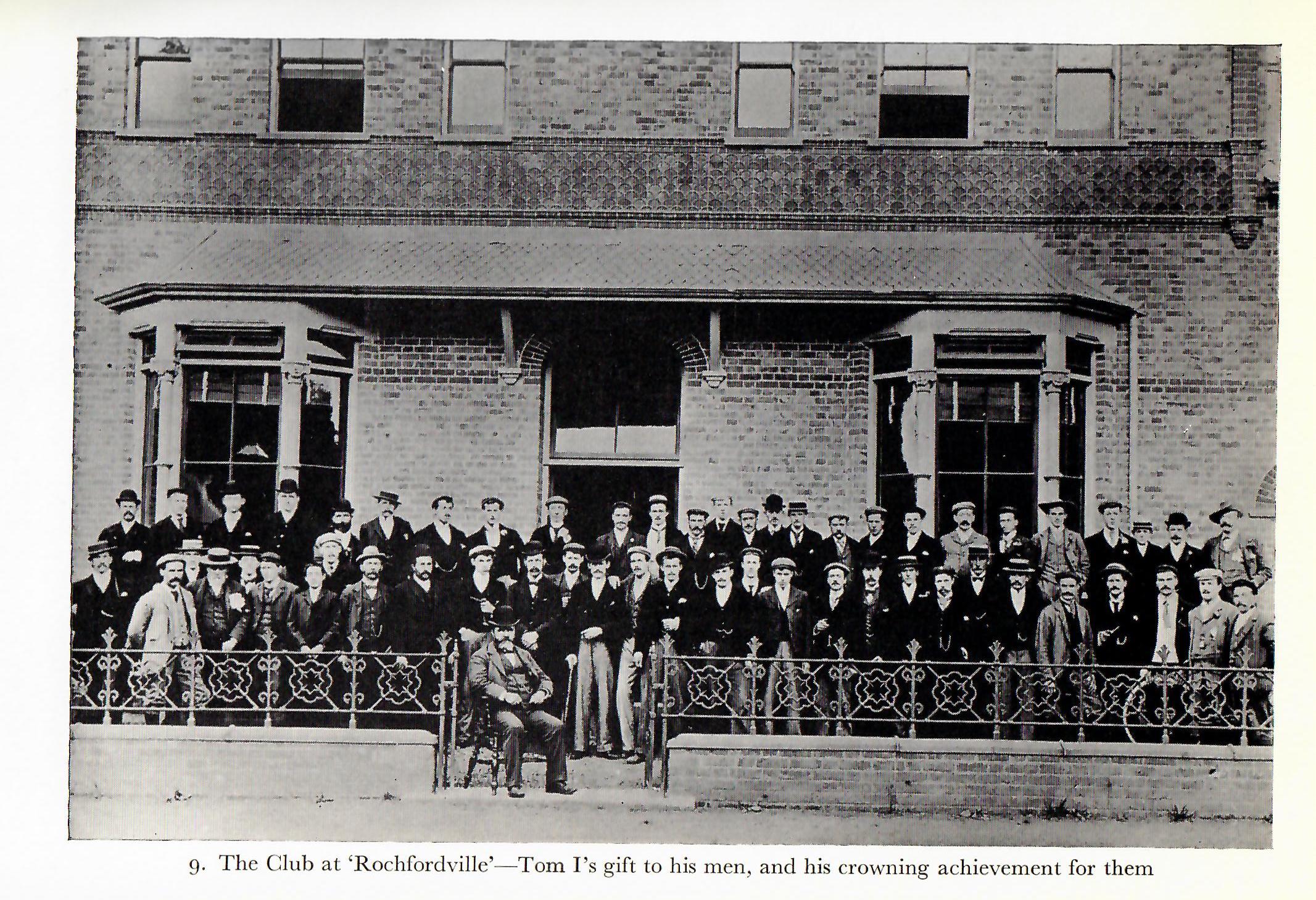

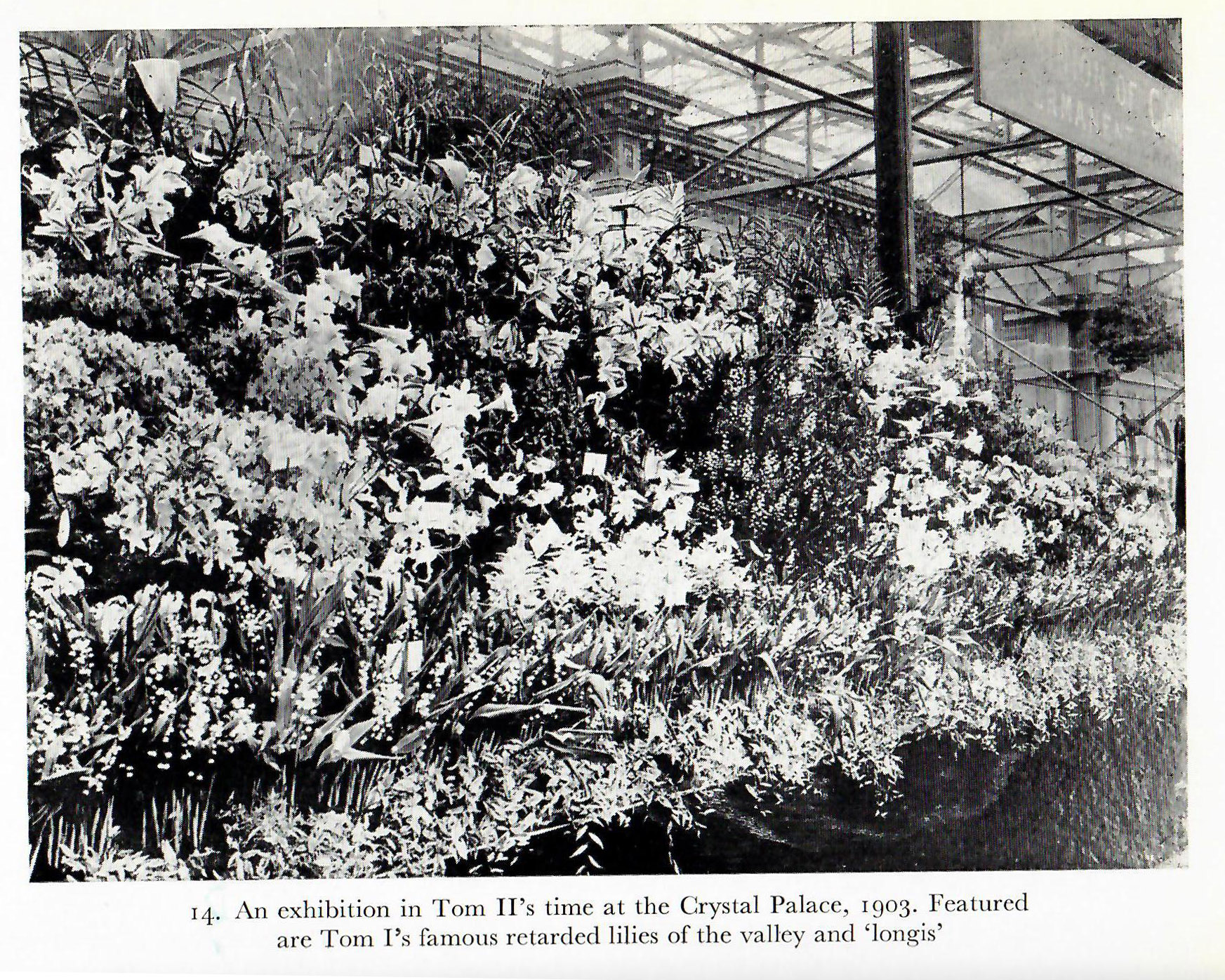

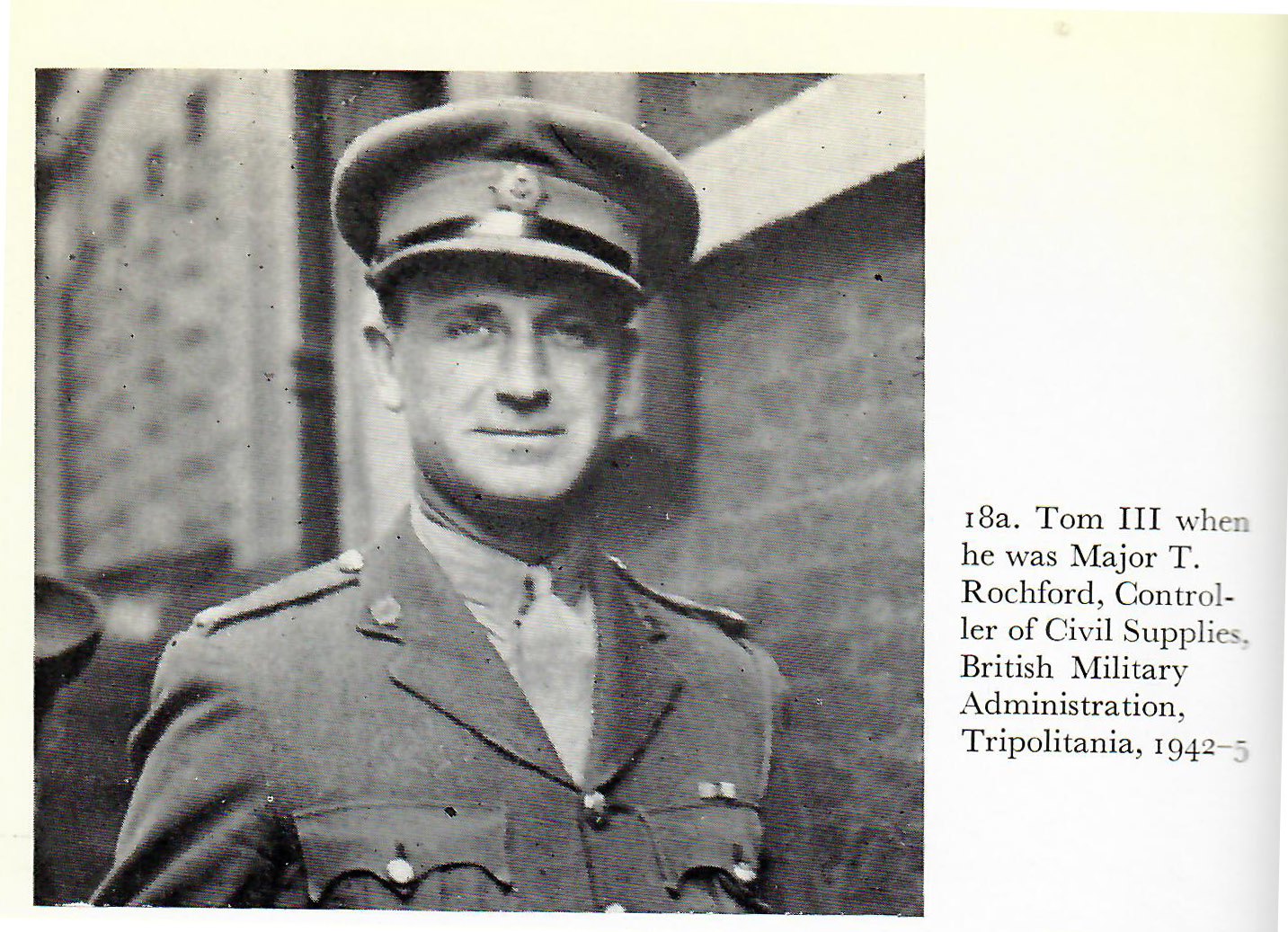

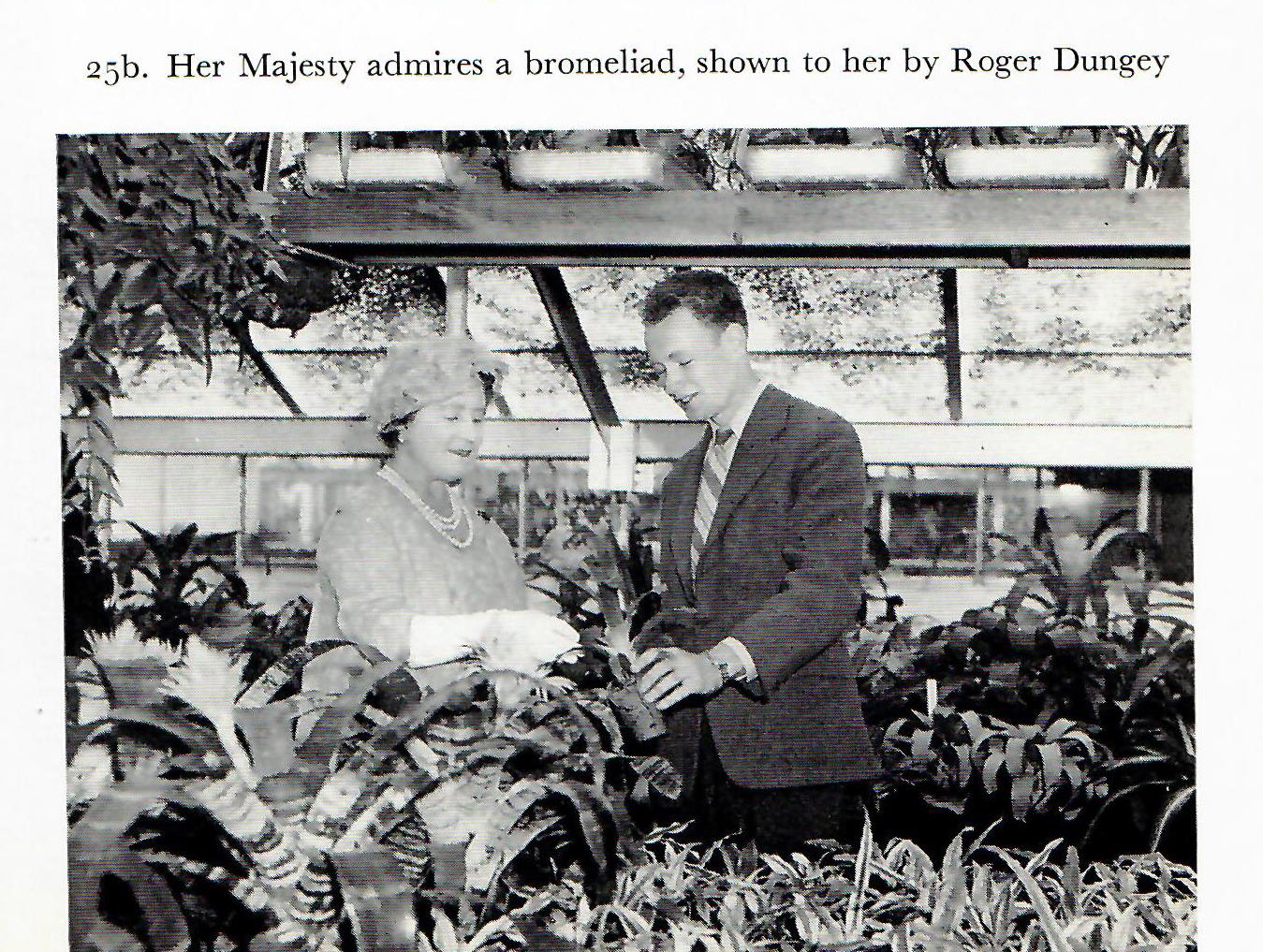

People of the Gardens: Five generations of the Rochford Family Click here for pics My father was a naval officer of the old school, immaculately turned out in uniform for every public occasion, complete with his gold-braided cap, starched collar, gleaming buttons, a white silk handkerchief in his top front pocket and on very formal occasion burdened by the naval sword that he had inherited from his own father. We were proud of him but kept our distance for he went poker-face solemn, would not hold our hands, let alone crack jokes and could not carry parcels on a public street, so we would trail behind him as baggage carriers. But back home in his own garden he was a man transformed, dressed in a worn old shirt and a battered pair of shorts, for ever up to something. Even for those who knew him well, it was a surprising contrast, this jolly contented figure with a clutter of forks, trowels, sieves, shovel and watering-cans bouncing around in a rusty wheelbarrow. He had undeniably green fingers, and an incredible ease with plants, and whichever naval base we were sent – Virginia, Malta, Gibraltar or the Highlands – he would renew the garden that we had inherited from a predecessor, knowing full well that in two or three years we would up sticks and leave it all behind. As children we all learned that watering plants in the evening (as you fed your animals) was one of the secret signs of a contented life. Our neighbours, especially in the somewhat stratified end of a foreign naval base, would wonder about this transformation, from starched-shirt officer to easy going redneck – for my father’s passionate immersion in gardening extended to splitting his own logs, building his own fences, chicken runs and planting his own trees. His explanation was simple “my mother was a Rochford.” *** For five generations the Rochford family had been plantsmen, building up the largest and most respected nursery business in London, then England, then the world. Their display at the Chelsea Flower Show was always the most jungle rich and opulent and invariably won them gold medals year after year and it was also their honour and delight to furnish the Royal Opera House with their plants and flowers. There was not a garden committee in the land on which some Rochford cousin did not sit, while Tom Rochford’s The Rochford Book of House Plants had become a recognized trade bible. The core of the family business was the Turnford Hall estate in London’s Lee Valley, where hundreds of acres of glasshouses nurtured plants and seedlings. The post-war boom in public housing had been good for business, for apartment block balconies and light-filled sitting rooms with big glass windows craved house plants. And over-love by over-watering meant that many of these plants were doomed and would have to be replaced in the following year. In the 1950s the Rochford catalogue listed 117 varieties and they sold a million potted plants a year. Twenty years later, the catalogue had trebled in size, with four hundred species. We could see all this passion for ourselves as children, for once a year the nurseries pitched a marquee on the lawn for the annual general meeting of its shareholders. We were always on our best behaviour, given a slap-up lunch and taken on a wonderland walking tour of the nurseries, which included Palm filled glasshouses that rivalled Kew gardens in their age and in the complexity of their environments, whilst the adults sat on chairs and listened to the annual report. Cheques to the various family shareholders were then amicably handed out, in sealed envelopes, by my father’s uncle, Tom Rochford, during the afternoon tea that ended the AGM. To my impressionable young eyes, at least half the Rochford shareholders appeared to be wearing dog-collars or nuns’ habits, and my father would give us a sotto-voice running commentary of the various good causes that were about to benefit from these annual cheques: orphanages in Africa, hospices in Liverpool and or eye-clinics in the Holy Land. I am afraid his cheque permitted us to be packed off to boarding schools, but nevertheless in all other ways it seemed to us the very model of an ethical family business, built up over five generations of hands-on work, and now supporting dozens of distant cousins to do good deeds with their share of the annual dividend. There was a plaque in the Rochford Institute, a club house for their workers, listing the three dozen young men from the nurseries who had died in the First World War and a long heritage of building good housing for the senior gardeners. The Rochford family were good employers and were staunchly Roman Catholic, sending generation after generation of their boys to be educated at the Benedictine Abbey of Ampleforth, after which some of them served in the Irish Guards. Father Julian Rochford, who taught physics at Ampleforth, was a living register of all this cousinage. Although the Rochfords were Irish, their first loyalty was always to the church rather than to the Republic. There is no paper trail for a genealogist to follow, but like the plot of a Thomas Hardy novel, they knew that although they were descended from a long line of hard-working peasants there was also the tiniest shimmer of old gilt about them from some distant past. Whether for real or in their imagination they looked back to a 14th-century heyday when they were in possession of slender tower-castles in the West of Ireland, held by such Anglo-Norman knights as Sir Richard Rochford, Sir Maurice Rochford and Sir Milo Rochford. The Rochfords (sometimes spelled De Rochefort) owned lands around Limerick, such as Crom and Adare, and these manors would be gifted to the Abbey of St Thomas in Dublin. As my father had it, “They bred like rabbits and became more Irish than the Irish, preferring to keep their faith at the cost of their castles, which would finally be blown apart by Cromwellians.” The Rochfords survived in the rough hill country of eastern County Clare, half-way between the shores of Lough Derg and the pretty market-town of Ennis. They worked the land in such townships as Knockbeha, Kilbagoon, Kilbarron, Fairhill, Curragh, though our lot came from a little place called Clandulla farmed by Thomas Rochford at the end of the 18th-century. Migration to America and Australia has taken the names of these sparse townships all the way around the world but the journey to England was less traumatic and could be seasonal. In the 19th-century ships ran from every Irish port and young men left home for a few months, joined the harvest or shearing gangs or worked some skill in a city and went back home for winter. The construction of the canals and docks in the 18th century and railways in the 19th century was achieved by armies of mobile Irish navvies. There was an established pattern of working relationships, which saw men from Ulster move to Glasgow, whilst Leinster (eastern Ireland) colonised Liverpool and Manchester, and Munster (south-western Ireland) was tied into the economy of Bristol and London. Letters of recommendation, trusted inns and landladies who ran boarding houses were the internet of that distant age. Michael Rochford, the twenty-year-old son of a farmer, would have fitted very easily into this pattern of migration, taking ship from Galway or Limerick to London. He probably had a letter of introduction, or someone who had already vouched for his enthusiasm and skills, for he found his first post in one of the most exciting botanical hotspots on the planet. In 1841 he was working at Joseph Knight’s Royal Exotic Nursery. This London nursery had been set up by Joseph Knight in 1808 after he bought Lord Dudley’s run-down London house (Stanley Grove in Chelsea) which already had a set of fine glass houses built by a previous tenant. Joseph Knight would have been a magnificent role model having risen through his own talents as a gardener at Woburn Abbey before being head-hunted by George Hibbert. Hibbert was a Jamaican sugar magnate who had enhanced his already considerable fortune by developing the West India docks in London and had always been fascinated by botany. On his own account or working with other patrons, he commissioned plant-hunters on a number of expeditions, making use of his existing merchantile connections, but he needed a top-rate gardener to take care of the specimens once they arrived back in London. Joseph Knight was just such a man, with his own genius for style and display and a canny eye for property development. The two men worked hand-in-glove for years, commissioning plant expeditions to South Africa, to the Southern states of the US and to Australia. Knight was also an indigenous English Roman Catholic, and in his old age used some of his fortune to endow schools and churches in his Lancashire homeland as well as setting up the Catholic community of St Marys in Chelsea in the 1840s. Michael Rochford would have felt doubly welcome in this environment. He lodged just round the corner from St Marys at 2, Symons Street with other young gardeners and the family of a Catholic bookseller. He stayed at the Royal Exotic Nursery for seven years, leaving just two years before Knight retired and handed the business on to his nephew. In 1848 Michael Rochford was offered the job of gardener for George Grenville (a radical-minded liberal MP and occasional civil servant, who inherited the title of Lord Nugent from his mother, whilst his fat and unpopular brother romped around the world as the Duke of Buckingham). Grenville needed a good man to revive the gardens around his Tudor mansion, The Lillies, in Weedon outside Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire, of which he wrote “in the days of its pride this blaze of flower-garden formed a rich contrast with the lawn of vivid green at the foot of the lowest terrace, which is itself culminated by a brook.” This promotion allowed Michael to propose marriage to his girlfriend, Sarah Mumford, the daughter of a Chelsea artist-craftsman, Joseph Mumford, who made those pretty block-printed wallpapers inspired by calico, expensive Chinese imports and Arras tapestries. They had their first child whilst working in Buckinghamshire for two years, but the death of kind old Lord Nugent saw them return to Chelsea. Through the recommendation of Joseph Knight’s Exotic Nursery in 1852, Michael Rochford became steward for Lord Feversham at Duncombe Park. This grand Yorkshire estate contained floral terraces, a six-acre walled garden, a free-standing orangery, an ionic rotunda, castle ruins and two conservatories (hothouse flowers in one, exotic fruits in the other). It was a lot of authority for a young man, but clearly Michael Rochford did well, for four years later Lord Feversham offered him another task. He had just bought Oak Hill in East Barnet, a celebrated estate whose working garden supplied London with exotic grapes and nine highly regarded varieties of pineapples (amongst them Queens, Providences, Brown and Striped Sugar-loaves, Globes and Antigua Queens) aside from the products of dedicated peach, cucumber and strawberry glasshouses. This was the golden age of the glasshouse which more than paid its way if quality was upheld. Rochford sold his grapes at 16 shillings against the normal market price of 1s6d, which brought in the near fabulous price of £1,800 a ton. Around £200,000 in today’s values. As well as running this self-sufficient garden kingdom, in 1857 Michael took a house and two-acre garden in Tottenham on his own behalf – 2, George Villas, Page Green. Using his savings, he constructed two glasshouses to grow his own grapes (chiefly Black Hamburgs and Muscats) for the market, assisted by a workforce of six men. The place had been spotted by his unmarried sister-in-law, Sara Mumford, who had worked next door as a monthly nurse, but now came into their household to help manage their seven children. Charles Baring Young bought Oak Hill off Lord Feversham in 1862 and not only kept Michael Rochford on, but leased the working areas of the garden to manage on his own behalf. In perhaps the same way that he found his first job in London, Michael kept a weather eye out for any useful job opportunities, so that the new butler and gardener appointed to manage Oak Hill both came from County Clare. Charles Baring Young (1801-1882) was a somewhat shy and scholarly offshoot of the famous London banking family. He and one of his sons collected medieval gospels and manuscripts which were given to Cambridge University in 1933, “probably the most valuable benefaction that the Library has ever received from any private individual in all its long history.” His other son, Charles Edmund Baring Young M.P. used his fortune to set up and endow two charitable schools, Oak Hill College and Kingham Hill, in England and Canada. Clearly a passion for gardening might helped identify a better sort of man, and Michael Rochford had the good fortune to work for a succession of employers inspiring in their sense of charity, responsibility and trust: Joseph Knight, George Grenville, Lord Feversham and Charles Baring Young. Michael Rochford was constantly adopting Victorian technical advances so that he could make use of better and cheaper glass, employ new and ever more efficient boilers, perfect new air circulating systems and water filterage. He was driven by the premiums for those who could deliver the first fruit crops and by a healthy air of gentle competition with other market-gardeners. He was also an inventive botanist, constantly looking at the workings of root systems and the ideal environments for plants to thrive. But it was not all rosy, and he was set back by the devastation of the 1860 hurricane and a glass shattering hail-storm of 1876. But the real threat to Victorian glasshouse culture was the efficient importation of fruit. First peaches and then the luxury prices achieved by homegrown pineapples were undercut and destroyed. Michael Rochford had been trading in Covent Garden market since his first days as a London gardener, and it is fascinating to see how efficient a well-run 19th century estate could be, both despatching fresh fruit and flowers to their owners’ household (when living in central London) and profitably disposing of the balance in Covent Garden. A combination of horse and cart (driven through the night) linking up to a pre-dawn train, saw products delivered all over Britain or to Covent Garden. The so-called Floral Hall that we can still delight in – built on the south side of the Royal Opera House after the 1856 fire – proved to be too successful an architectural space and instead of being rented out to flower sellers became a concert hall and bar, so another New Flower Market was created further south. When this opened in 1871, Michael Rochford took stand no 279, later expanding to three stands in a row, 81, 82 and 83. He could not rid himself of his lifelong obsession with homegrown grapes but otherwise moved quickly to replace glasshouse-grown fruit with ferns, lilies and a succession of flowering and scented shrubs to punctuate the London seasons. He also made certain that the Rochford stands at the Royal Horticultural midsummer show and the Royal Botanic Society’s Regents Park exhibition caught and kept the eye. His five sons were folded into the business, and once old enough were sent off to learn new tricks while working three-year apprenticeships in rival nurseries. Tom, the eldest Rochford boy, had married Mary Ann Agnes, daughter of Samuel Straight who dealt in ivory and pearls at 35, Charles Street, Hatton Garden, concentrating on broaches, earings, ivory combs, hair brushes and statuettes, whilst he and his brother (another Thomas) ran a wholesale ivory business at 12, Walbrook, Wapping specializing in the vast (but competitive) trade in piano keys. It was his parents-in-law, not his father, who lent young Tom Rochford the money to set up his own nursery in Tottenham in 1876 (where the Hotspurs Stadium would later rise). After the death of Michael Rochford in 1883, Tom and his equally talented brother Joseph bought two adjoining lots from the sale of the Turnford Hall estate. In 1887 the brothers bid against each other, as to who would buy Turnford Hall (once the old Black Bull coaching inn) but otherwise divided their world between fruit (Joseph) and flowers (Tom). Every year either one or the other would buy another plot of land, building more glasshouses, then recoup their money, before plotting the next expansion. By 1898, they had eighty-six acres under glass, ten miles long if placed end-to-end and employed four hundred workers. They set up the Rochford Institute as a self-governing club house for their workers and built them decent housing. The area was nicknamed Rochfordville. Tom Rochford I died relatively young (aged 56) but his will bound his experienced brothers into assisting his chosen heir, a son, also called Tom (II). In the First World War, the family put their vast inheritance of flowers, ferns and palms to one side, in order to grow cucumbers and tomatoes to feed the coal miners. Many of the male members of this by now very large family fought in the war, and those that survived came back physically and mentally damaged (Harry lost an arm, Charles had been pierced by a shell and Ernest experienced the horror of fighting in Salonika). Tom Rochford II died early as well, in 1918, leaving a 13-year-old son and his war-battered uncles trying to hold the business together, seeking the advice, but also fearing the authority of the last surviving member of the older generation – Joseph Rochford – who had done very well in London property development whilst also keeping his own nursery business. Tom III was just beginning to get to grips with his tangled inheritance, slightly burdened with well-meaning but half-hearted cousins on the board, when he was called up to fight in the Second World War. The army for once got the measure of their man, and Major Thomas Rochford ended up as a benign but efficient member of the British Military Administration, feeding and assisting the war-battered population of Libya from 1942-45. He married a woman, who had also proved her mettle in the war, Section Officer Elizabeth Mary Ford Duncanson of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. They needed all these leadership skills to revive Rochfords, now a series of run-down compounds mismanaged by instructions from wartime ministries. It was not until 1951 that Tom III succeeded in restoring the building stock and in patiently redirecting the business towards new, smaller breeds of house plants – initially nicknamed Tom’s Weeds by the workforce – for he was aware that more and more of the population would become flat-dwellers. His exhibition stands during the 1952 Festival of Britain year, then the following season at Chelsea, showed the world that he was on to something, assisted by the dazzling displays developed by his young wife. Betty was quickly made a director in her own right. They went on fact-finding missions to explore what was happening in the world, especially in the USA, not just in terms of new tastes, but in how to best package, transport, present and promote. Within twenty-five years, their vision was rewarded, and between them they created the world’s biggest house-plant business, winning gold medals and awards, year after year. The Queen Mother even arranged to have a tour of the Rochford Nurseries. But this edifice, built up by generations of dedicated labour, was not to last. Tom’s son and heir was highly educated, but he was not a plantsman. Instead all his analytical, number-crunching skills showed him that once England entered the EEC, Rochfords were going to be undercut by cheap imports from Holland, and that it was better to sell whilst there was something still of value, rather than slowly go to the wall. The glasshouses occupied valuable building land, so every cousin got a handsome cheque to make their own magical garden. I believe Joseph Rochford Nurseries are still in business in Hertfordshire, but otherwise all had been swept away, with only a road sign, Thomas Rochford Way, to show what there once was. Fortunately there are a number of books, such as Mea Allan’s Tom’s Weeds: the story of Rochfords & their House Plants as well as Tom Rochford’s three plant books published by Faber. They were all co-authored with Richard Gorer: The Rochford Book of House-plants, (1961), Rochford's Book of Flowering Pot-plants, (1966) and Rochford's House-plants for Everyone (1969). Tom’s children remembered Richard as a frequent guest, albeit a somewhat shabbily dressed professor type who could reel off even more Latin names than their father. Richard Gorer was outwardly a shy polymath, a distinguished musicologist and horticulturist who had studied at Kings College Cambridge before the war. Richard’s father had dealt in Oriental work of art and his two brothers were public intellectuals: Geoffrey Gorer, a distinguished anthropologist and a travel writer (whose book Africa Dances we publish) and Peter Gorer, an immunologist whose work pioneered the first organ transplants. Richard was much the shyest of the three brothers, and after the death of his mother shared a cottage with two friends, Billy Ledger and Paddy Ross in the days when it was still a crime to be openly homosexual. The three men ran a market garden that Richard had acquired, and their friends included the writer Angus Wilson and John Hooper Harvey, the founder of the Garden History Society. The cottage was fabulously disordered, with piles of horticultural journals fighting for space with unwashed glasses and muddy boots, but the walls were dominated by the canvases of Francis Bacon.

Tom Rochford III’s elder sister, Gertrude, was my father’s mother. She died just before the Second World War when he was ten, after which her husband was called back into the Navy from the retirement list, and two years later, my father joined the Navy as a boy cadet. Gardening like a Rochford was not the only link that kept my father close to the animating spirit of his mother, for he also inherited her loyalty to the Roman Catholic church, but in all other ways was almost a caricature of an Englishman. But he delighted in Covent Garden, and fortunately for us would proudly show us that it was part of our heritage, and take us round those chaotically animated streets while they were still busy with flower and fruit sellers, two great theatres, half a dozen publishers offices (perched up in the attics with their cheap rents) and a wonderful mixture of the louche, the hard-working and the urbane. It certainly made watching My Fair Lady something of a family cult, and we would speculate about where the Rochford flower stands would have been. But over a history of five generations, the answer was that the Rochford stands moved around a lot. And then it was time for our favourite story, about a blind old member of the Rochford family, who would insist that she be brought down to the market, and from the scent of the predominant flowers, could immediately summon the hierarchy of seasonal scents, which culminated with lavender which marked the end of the London season.

|

Recent Books |