| HOME | About Barnaby | Books | Gallery | Reviews | Articles | Talks | Reading List | Links | Contact Info |

|

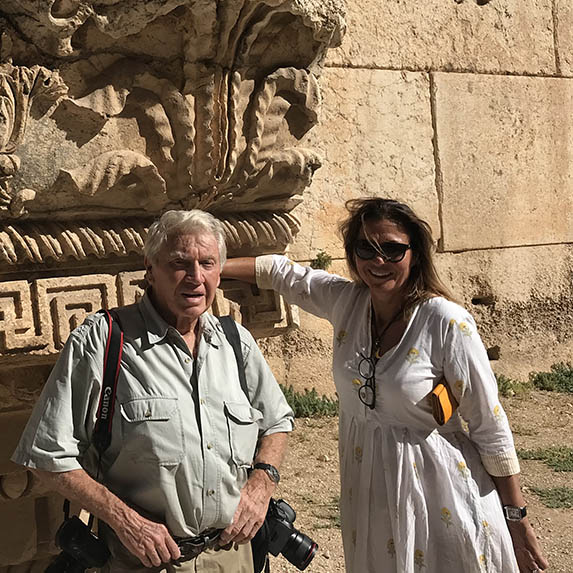

Travelling with Don McCullin in Lebanon

Don McCullin is one of the world’s most famous photographers, yet he’s always happy to bed down in this kind of simple hostel when there’s a picture to be captured. He is an artist with the internal discipline of a master craftsman. Lean and still horribly good looking, his thick mop of silver hair crowns a tanned face lit by a pair of startling blue eyes. Perhaps the easiest way to describe him is Michael Caine crossed with Steve McQueen. If you want to find out what it is like to be invisible, all you have to do is to walk into a bar beside him. He is a babe magnet of the first order. I still chuckle in delight at the memory of being pushed expertly to one side by a skilful hand, as the other popped a telephone number in Don’s top pocket, alongside a silky little whisper, ‘Call me.’ I am a plump, balding publisher of travel books with an immense capacity for wine, parties and picnics. We make an odd pair of travellers. One of us is armed with a neat, almost military cannister-box full of camera lens, the other burdened by bags of books, badly-folded maps, dog-eared pamphlets and one or two emergency items, such as a cork-screw and a hat. But driven by a shared passion for the ruins of the Roman empire – the contours of a time-battered portrait bust, a limbless god, a temple tottering towards oblivion, a theatre slowly cascading down the hillside which it once framed – we travel well together. Once on site, we completely ignore each other. I scamper about, ‘surprisingly agile for a man of your size’, walking my way into knowledge of the landscape and talking to archaeologists when they will put up with me. Don is like a man possessed, pacing around a much tighter focus, as he battles in his mind with shifting patterns of light, shadow, clouds, perspective and composition. We seldom make a plan, let alone communicate by phone, for we understand that neither of us will have finished until we are finished. Occasionally I hear Don’s powerful whistle, which he makes use of for one purpose and one purpose only – ‘get out of my line of sight’. Only in the burnt-out light of midday, or when it is dark, do we talk. He is a brilliant mimic and has worked with almost all my travel-writer heroes. Out come stories about adventures with Norman Lewis, Eric Newby, Bruce Chatwin and Brigid Keenan, who first introduced us, complete with Don’s startling evocation of their voices. It is through Don that I first met such real adventurers as Mark Shand and Charles Glass. Don, now Sir Don, eighty-four years old, has recently had an extraordinary solo exhibition at Tate Britain. We have done journeys together in the Libya, Algeria and Turkey, and this time we were in Lebanon, beginning with a weekend in Beirut, where Don opened the Art Fair with a lecture. In the auditorium, as Don took the audience through images from his personal witnessing of some of the worst horror stories of our era – Biafra, Cyprus, the Congo, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Cambodia, Northern Ireland – there was a hum of liberal concern. I am convinced that historians will look back on the late 20th-century as one of the golden ages of mankind, like the Antonine period of the Roman empire. They were both eras of peace, freedom, continual growth and prosperity. But at times like this, it becomes brutally clear that although this might be true for the West, it was not always so for the rest world. Suddenly, the mood shifted. The audience, as one, sat bolt upright and held their breath. The chuckling, scented warmth of the Levant was cold and silent. The image that Don had projected onto the screen was of a beautiful, ardent young Lebanese woman in tight jeans, throwing a hand grenade from the balcony of a hotel in Beirut. The audience, which had hitherto been bowled along with the confidence of the Art Fair and bewitched by Don’s beautifully composed Pieta of world suffering, was suddenly brought short. It was no longer Paris-New York-London-Rome-Beirut, but something darker. Only a block back from the luxury hotels and inaccessibly chic nightclubs of Beirut, hovering in the shadows, are the vivid scars of the Lebanese Civil War. It was just a brief, spontaneous wince of pain before the audience once more assumed the face of amused confidence. But Lebanon being Lebanon, that was not the end of the story. Just as Don’s talk was over, someone stood up from the audience and handed him their mobile telephone. On the other end was the young woman with the hand grenade (a female Arab Discobulus for our time) wishing to have a quick, last word. After they had finished talking, a large man came up and embraced Don and talked briefly about his work running an Interfaith Cultural Foundation. He looked a jovial, saintly type and I noticed that most of the audience were standing up and smiling at this public encounter, and the cameras were clicking. Thirty years ago, he had been the commander of one of the more notorious militia groups. On this trip, Don’s beautiful wife Catherine had joined us. I liked her input, which got us swimming in the sea between medieval turrets at Tyre and a useful upgrade in the quality of hotel bedrooms. On our last night in Lebanon, we ate fish in a restaurant built on wooden stilts over the sea, beside the Phoenician walls at Al Batroun. There were no other travellers, though the current street unrest had not yet begun, and the only interruption to our meal had been from scuba divers emerging from the sea to bring the evening catch to the kitchen. We had already had enough to drink, but ordered up another bottle of the local pink to be absolutely sure. The conversation came round to heroes, and I confessed that the closer I got to know many a writer (as opposed to their work), the less likely I was to continue admiring them. I turned to Don and asked him if he too was running out of heroes. There was something in the rapidity and confidence of his reply that reminded me of the exceptional nature of the man I had been travelling with these last ten days – the composers Purcell and Bach, the writer Primo Levi, Daniel Barenboim and Yacoub (an Egyptian heart specialist). His wife joined in, confessing that for all his faults she loved Jonathan Miller, then added, ‘I could never go back to public school boys, not after Don.’ LEBANON, Travellers Fact Box

The National Museum in Beirut is a wonderful, carefully selected gathering of five thousand years of artefacts, sculpture, jewellery, mosaics and frescos. It is both an aesthetic treat and a deep historical immersion. Both of us, at different times and with different people, had been to the Temple of Baalbek. But the more you get to know this temple – one of the ten wonders of the ancient world – the more it calls you back, as you realise what you have missed. We were also determined to stay at Baalbek’s Palmyra Hotel, one of the last of the old turn-of-the-century hotels to have survived and kept its character. The third must-see was Byblos, a dusty-looking archaeological site beneath an impressive looking Crusader castle, which has the most astonishing variety of historical levels and occupation that you will ever encounter. Walk twenty paces and you find yourself travelling a thousand years. By great good fortune, and thanks to our efficient driver, we also managed to see everything on our wish list: the Crusader castle at Beaufort, the Roman circus track at Tyre, the temple at Niha, the old city of Sidon, the Holy Valley of the Maronite Christians and the old city of Tripoli. There’s still plenty left for the next trip. The political situation is lively at the moment, with street demonstrations against government corruption and inefficiency. Nevertheless, the democratically elected government of the Lebanon is one of the surviving miracles of the Middle East, a constitutional coalition of ethnic communities: Maronite Christians, Sunni Muslims, the Druze and Shia Muslims. On top of this, there are hundreds of thousands of refugees from Palestine in the camps they have been living in since as far back as 1948, and millions of more recent Syrians refugees, not to mention Israeli jets streaming in from the south to show their power. Saudi Arabia and its Gulf partners are largely underwriting the rebuilding of Lebanon after the destruction of the civil war (1975–1990). Everywhere we went the food was astonishingly fresh and good. Hotels are expensive, charging the same as you would pay in the Gulf or the USA, dollars accepted. The best English guide book is published by Bradt, and I strongly recommend the anthology "Lebanon: through writers’ eyes by Ted Gorton and Andree Feghali Gorton", published by Eland (where I work). Share

|

Recent Books |

On the first morning of a recent two-week trip, I knocked lightly on the door of Don McCullin’s room to check he was up. It was dark, and we were hoping to catch a nearby temple in the first light of dawn. The door immediately swung open, and Don appeared, bags packed, camera case to the fore. The shadow of a grin crept across his face as he met my glance. ‘Up at last I see,’ he said. ‘Only you could have slept through your mate making such a din.’ The mate he was referring to was the muezzin, calling the dawn prayer.

On the first morning of a recent two-week trip, I knocked lightly on the door of Don McCullin’s room to check he was up. It was dark, and we were hoping to catch a nearby temple in the first light of dawn. The door immediately swung open, and Don appeared, bags packed, camera case to the fore. The shadow of a grin crept across his face as he met my glance. ‘Up at last I see,’ he said. ‘Only you could have slept through your mate making such a din.’ The mate he was referring to was the muezzin, calling the dawn prayer.

Don and I had a hit list of three things we had to see and a further handful we wanted to see if the situation on the ground permitted.

Don and I had a hit list of three things we had to see and a further handful we wanted to see if the situation on the ground permitted.