| HOME | About Barnaby | Books | Gallery | Reviews | Articles | Talks | Reading List | Links | Contact Info |

|

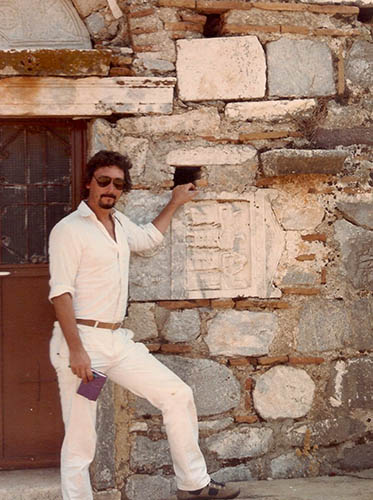

MICHAEL HAAG Michael Haag, who wrote the obituary of Ralph Bagnold in the last Eland newsletter, was himself a writer, a traveller and a publisher. Like us he first got into the game by putting together guidebooks. His Cadogan guide to Egypt was first rate. Michael was both amused and world-weary at the same time and his eyes would flash open with passionate interest before glazing over like a lizard. He spoke with an odd, almost Damon-Runyan lisp, as if always delivering a stubby punch line.

Michael grew up in New York but first came to England aged three on one of the first post-war ocean liner sailings to Europe in 1946. He was a traveller from then on, and because his father worked for an airline he made repeated visits to London throughout his youth. At school in New York City he was introduced to esoteric literature – notably to Robert Graves’s book The White Goddess – by a slightly older school friend, Sterling Morrison, who was later one of the founders of Velvet Underground. Michael went on to Boston University. But he was always a mischievous prankster and after several incidents he was expelled. He tried to fit into the University of California at Berkeley, but in 1963, he came over to stay with his aunt in Maida Vale, and enrolled at London University to study anthropology. He later found a job working in London for an organisation called BUNAC, which specialised in student work placements in America. BUNAC published a simple travel guide to North America and, as part of his duties, Michael was asked to revise it, which he duly did, transforming it into a proper book. He then singlehandedly wrote a BUNAC guide to the entire Mediterranean. This was the real start of his career as a writer, and all his historical interests began to come together – along with a lifetime passion for Greece and Egypt. At some point in the 1970s, BUNAC was acquired by an airline company called Court Line – the Easy Jet of its time – and the travel guides along with it. In 1974 Court Line went bankrupt and Michael was out of a job, but was able to buy the travel guide part of the business at a rock-bottom price. And so he embarked on a parallel career as a publisher, writing a dauntingly good Guide to Greece and an even better one to Egypt. In 1982 he started reprinting appropriate travel books and after five years had built up a list trading under his own name. In those innocent days it was possible to contact an author by looking them up in the London telephone directory. When Michael sold his business, his guidebooks would be picked up by Cadogan, while the travel books were rebranded under Immel, and he could concentrate on his own writing. His lifelong fascination with Forster, Cavafy and Lawrence Durrell culminated in a substantial work, Alexandria City of Memory, a wonderfully rich, evocative book, full of layers of history. It was dedicated to Loutfia, his second wife, who was a wonderful enthusiast. She tried to help me round up a sufficient number of her cousins in Cairo to get the publishing rights to the Saharan travels of her grandfather, Ahmed Hassenein Bey. It proved too complicated, for they feared that I wanted money from them, and could not believe that we intended to pay them royalties. I can still hear Michael’s knowing guffaw. Later Loutfia admitted to me that there were probably other complications. Her family felt that they had to abandon their past under Nasser. Hassenein Bey had been a Balliol-educated member of the old regime and rose to become Chamberlain and the trusted confidante of the Queen Mother of Egypt. He had been a former-person under the Republic. Then an old publishing friend persuaded Michael to write a guide to the best-selling novel, The Da Vinci Code. The only problem was that it had to be done at great speed, so helped by his wife and daughter and gallons of coffee they composed it in a fortnight. It was much more interesting than Dan Brown’s original, full of strange, arcane historical knowledge. It sold 160,000 copies, which bought Michael the time to do books that he really wanted to write, including one on the Templar Knights, one on the Durrell family and continue his research into his biography of Laurence Durrell who remained his role model as a writer and as a man. Mark Ellingham delivered a loving and funny obituary at Michael’s funeral, from which I have extracted these facts. He was Michael’s friend, fan, publisher and enabler. Like ourselves and Michael, Mark also started out in guidebooks, writing one to Greece, one to Morocco and setting up Rough Guides in the process. All four of us shared the experience of being paid a pittance to explore and take notes, and we also had the privilege of time, spending months rather than weeks getting to know a country, and then returning to do an update, exploring in greater depth and revisiting favourite places. We would all agree, that one of the most acute pleasures of the traveller with time on his hands is reading the right book in the right place ¬– discovering stories in the landscape in which they were written.

|

Recent Books |

When we were thinking of setting up in business, he invited us to supper in his basement flat in North London so that he could share his experience of running a small literary list. It was a memorable evening, for his Egyptian wife Loutfia played a hand drum between courses, his friend Justin told us horrifying stories about Vietnam and we drank a lot of red wine while trying to remain balanced on red leather poufs. The core of his advice was to not get divorced, for in his case it had taken away the London family home the value upheld the large overdraft needed to support the outgoings of a small publisher. But Michael had paid off every last penny he owed to his printers by selling his publishing company to a businessman from Saudi Arabia who loved books but did not understand the need to sell them or open letters, let alone reply to them. With Michael’s advice we eventually got hold of one of the jewels in his list which was Ralph Bagnold’s Libyan Sands, after it had languished in legal limbo during the slow ossification of his old business. He also published T E Lawrence’s Crusader Castles and E M Forster’s guidebook to Alexandria, Pharos and Pharillon. I was mightily intrigued by both books, but in the end you realise that they hide more than they reveal. The only other books in his list that were really outstanding were Dilys Powell’s two Greek books: A Villa Ariadne and An Affair of the Heart. We admired them from afar for decades but have finally managed to add them to the Eland list.

When we were thinking of setting up in business, he invited us to supper in his basement flat in North London so that he could share his experience of running a small literary list. It was a memorable evening, for his Egyptian wife Loutfia played a hand drum between courses, his friend Justin told us horrifying stories about Vietnam and we drank a lot of red wine while trying to remain balanced on red leather poufs. The core of his advice was to not get divorced, for in his case it had taken away the London family home the value upheld the large overdraft needed to support the outgoings of a small publisher. But Michael had paid off every last penny he owed to his printers by selling his publishing company to a businessman from Saudi Arabia who loved books but did not understand the need to sell them or open letters, let alone reply to them. With Michael’s advice we eventually got hold of one of the jewels in his list which was Ralph Bagnold’s Libyan Sands, after it had languished in legal limbo during the slow ossification of his old business. He also published T E Lawrence’s Crusader Castles and E M Forster’s guidebook to Alexandria, Pharos and Pharillon. I was mightily intrigued by both books, but in the end you realise that they hide more than they reveal. The only other books in his list that were really outstanding were Dilys Powell’s two Greek books: A Villa Ariadne and An Affair of the Heart. We admired them from afar for decades but have finally managed to add them to the Eland list.