| HOME | About Barnaby | Books | Gallery | Reviews | Articles | Talks | Reading List | Links | Contact Info |

|

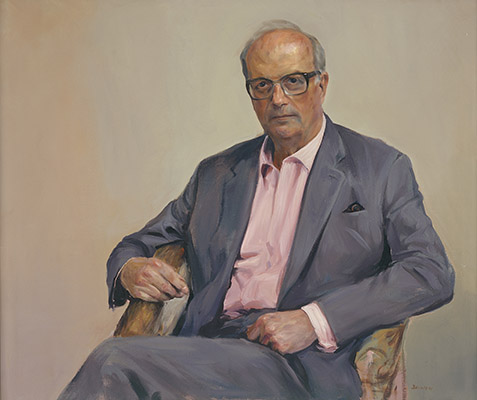

JOHN BARING (LORD ASHBURTON) John Baring was an example to us all. He was hard-working, decent, generous and incorruptible. He was an Englishman whose word was his bond. He was a patrician who delighted in his estate, his garden, his family and his wife Sally. On a first meeting he could appear rather aloof and cold for was incredibly tall and thin with owl like eyes that missed nothing. He was discrete to the point of being secretive which came with the job of being a banker to Kingdoms and a friend of monarchs. He also understood finance and the need to protect currencies from the manipulations of politicians. He was suspicious of the expertise of the media yet always read the papers with passionate attention, "for they always sound well informed until you read something that you know about". He believed in God and was a loyal member of the Church of England, quietly proud of his annual day parading as a Knight of the Garter in Windsor and as honorary treasurer to Winchester Cathedral. After the death of his father, he became a Baron, the seventh Lord Ashburton.

He was a countryman whose favourite time for a walk was at dusk, alone in order to catch the wildlife busy about their work. He was incredibly knowledgeable about trees, which he could identify if you brought him even a single leaf, and he knew not just about birds but their habits and their seasons. If he had a hobby it was either rivers (he owned sections of the Candover and the Itchen) balanced by a lifelong delight in watercolours. He tried his hand painting in retirement (alongside his wife Sally) which he balanced with collecting traditional English watercolours with great discernment. He had a curious and special empathy with amphibians and reptiles. His eyes lit up with delight in the company of newts, frogs, toads and snakes. He gave academic and conservation organisations open access to do research on the estate and was delighted to study their researches; from looking at silt in the lakes to determining the rate of nutrient deposition of historic farming practices, analysing and mapping 18th and 19th century water-meadow systems and a comprehensive survey looking for rare aquatic invertebrates found only in winterbournes. The estate was found to be 'one of the last breeding grounds in the south of England of the threatened white-Clawed crayfish' and would provide the brood-stock for the establishment of ark sites elsewhere. He shared these passions with his sons, who remembered his delight in the technical issues behind scientific enquiry. As a young man he built a .410 pistol from an old shotgun to use from the seat of the combine harvester for shooting rabbits fleeing from the diminishing cover in a wheat field during harvest. He preferred a properly organized briefing paper to a live debate, but he knew how to control and shape a meeting. The opposition would be given the conversational rope in which to hang themselves, while he kept his silence until pressed to give his opinion, which invariably was short, sharp and to the point, and which inevitably ended up being accepted as the chairman's summary. Only a month before he died, aged 91, he had finally completed negotiations with his four business partners (his two daughters and two sons) to build a new winery for the Grange vineyard, hived off from a corner of the estate. He was a Baring first and foremost, though through his mother Doris Harcourt, his grandmother Mabel Hood and his great-grandmother, Leonara Digby he was related to most of the grandees in the British Isles. Distant Baring cousins would be encouraged to remain part of the family, and asked to join in the shoot or stay for the weekend to attend the summer Opera. When his father and aunts were alive, they would always be included in Sunday lunch, unless they were dining with his brother Robin Baring, the artistic heir of Cecil Collins married to the writer Anne Gage. He delighted serving his guests good wine to the extent that he never understood the charm of a pub and looked out of place at a beach picnic. His puritanical streak emerged every year with his annual attempt to cancel the fuss of Christmas. His favourite season was the autumn, 'after the harvest is in and counted and with the shoots to look forward to.' I noticed that two of his best friends, Lord Sainsbury and Lord Airlie, both shared his passion for work and his sense of obligation and were also powerful patriarchs of extended families. John won the nickname of Basher Baring from vocal conservationists in the press. To the public he did indeed seem the arch villain, who had knocked down Stratton Park, and was intending to do the same to the Grange Park. The story is more complicated. He and his father had privately offered the Grange to the nation, repeating an offer an even more generous offer that had been made by the previous owner, Charles Wallach (complete with its pictures). Both of them had been turned down. However the press furore against Basher Baring did serve its purpose, giving the politicians the right mood in which to step forward and save the House for the Nation. To his own family he was not a Basher but a compulsive Builder. He is the only man of his generation to have commissioned and built two contemporary country houses. For the portico of Stratton Park was the frame for a visionary modernist house of glass and concrete and fish ponds created by Stephen Gardiner and Christopher Knight. When the M3 was pushed through the back garden, John decided to build again on the other side of the water from The Grange. Francis Pollen's Lake House is almost Japanese in the purity of its lines and texture, but filleted with pared down classical details, and imaginatively placed beside the old walled garden. In France, he bought the farmhouse belonging to Sally's stepmother, and then gradually acquired adjacent cottages and barns in order to extend La Maison Rose over a quarter of the old village. His final building project, was to aid, encourage and assist Wasfi Kani, into turning the old orangery of the Grange into a state of the art theatre for her summer Opera festival. This dream team worked well together for eighteen years, before finally falling out, and going their own ways. Then he and Sally were back at work, helping Mark Baring set up the Grange Festival under the direction of Michael Moody and Michael Chance. John Baring worked for Barings Bank all his life, commuting on the central line underground with 'his ball and chain' a great black attache case, weighed down with papers. His distant ancestors had been too rich to do anything apart from shoot and sail around the world in their private steam yachts. They lived in Bath House in Picadilly, had a Norfolk estate as well as fishing lodge sin Scotland and Devon aside from the Grange at the centre of a 40,000 acre estate in Hampshire. But his grandfather Frank succeeded in consuming this inheritance, leaving his daughters virtually penniless. John worked at Barings Bank for good reason, as had his father, Alec Ashburton. John started a three year apprenticeship at Barings as a 22 year old, topped up with a period in New York. He did not see eye to eye with Lord Cromer but once this distant cousin had been promoted to become our ambassador in Washington, he became a Director aged just 27. A position that had never been offered to his own father. He was Chairman of Barings from 1974 to 1989, which crossed over with his role as a Director of the Bank of England from 1983-1991. When he resigned as Chairman he could look back over an extraordinary period of growth. When he joined the Bank it employed 200 staff with a balance sheet of £30 million, when he left this had grown to 2,400 employees and a balance sheet of £3 billion. John's father Alec Ashburton had managed to keep hold of some marginal farmland around Itchenstoke as a remnant of his ancestors once vast landholdings in Hampshire. So when the Grange Estate came back on the market in 1964, father and son were able to think about trying to buy it back. They asked an agent to bid at the public auction at Winchester, while father and son stood modestly at the back, pretending to be innocent bystanders. When the hammer fell, they found that the entire room had risen, turned around and was applauding them. After a forty year interregnum, the Barings, had got themselves back on their feet. A few years later John helped create the Baring Foundation (a charity that gave away the Banks profits) and in 1969 succeeded in transferring the ownership of the Bank to this charity. It was not all totally altruistic, for in France the socialists were nationalising private merchant banks and this move would frustrate any squeezing of the rich until the pips squeak. But be that as it may, it worked. By 1995 the Baring Foundation had grown into the 10th largest grant-giving charity in the UK. The sudden internal collapse of the Baring Bank due to a trader trying to hide his losses (in the toxic world of financial futures) was a double tragedy. It had happened before (over Argentine railway stock) and ten years later all sorts and conditions of Banks would go under, but on that occasion governments stepped in, and did not stand by and watch. After retiring as Chairman of Barings John had an extraordinary second career as Chairman of B.P. For it fell to him, as Senior Director to mount the boardroom coup of 1992 that sacked Bob Horton, the brilliant but by then out of control chief executive of both Standard Oil and B.P. John confessed that it was 'the most frightening thing that he had ever done' although he also proudly bore the scars of a head on confrontation with Dennis Healey when Chancellor of the Exchequer. Other Chancellors, such as Geoffrey Howe were not so much colleagues as friends. John joined the House of Lords as a hereditary peer in 1992 and controversially made his maiden speech the day after he took the oath. In those days you were expected to listen and soak up the courtly manners for some months. But he couldn't resist the chance to talk about banking and exemplify his lordly style of courtesy and razor sharp wit immediately. He had strong views about Europe, being a Europhile but was against the UK joining the Euro. But he became so infuriated at the political manipulation of their own fiscal rules (in order to expand the Euro-zone) that he reluctantly lots confidence in the whole project and voted for Brexit. He also spoke about House of Lords reform, suggesting that 'the House of Correction' might be a good name for the upper chamber. But when hereditary peers had to stand for election to stay in the Lords, he could not find it in himself to canvass and was evicted along with 90% of his fellow peers. This was a pity, for when he put his mind to it, he was a very gifted speach-maker. But in his retirement he put these skills to work at opening nights at the Grange Opera, accompanied on the stage by Bessy, the most beloved of all his black Labradors. John was first married to the beautiful Susan Renwick, daughter of the Lord Renwick, whilst his best friend from Eton, the handsome athelete Antony Rowe married her sister Jenny. They had four children, Lucy (who created the Vaughan lamp empire with her husband Michael), Mark (who worked at Barings and now manages the Grange Estate), Rose - a Russian speaking psychotherapist who also runs Eland publishing) and Zam (who made documentary films before he ran the Grange vineyard). Susan and John divorced, after which John married Sally Churchill, the divorced wife of his old friend, Colin Crewe. His children breathed the sigh of relief, for there had been some alarming other candidates whilst Sally had been a happy presence on family holidays throughout their childhood. Sally had her own three children (Peregrine 'PG', Emma and Bel) and was determined to retain her independence as a designer and having sold her dress designing business "Sally Spencer" set up Borderlines to design fabrics. John came on board as a financial advisor and for the US sales trips. On his 80th birthday they rented two gulets in order to cruise the Turkish coast with enough cabins to accomodate their thirty-one children, grandchildren and assorted partners. Travel had always been a cherished part of John's life. He had driven across the states as a young man with the art historian Nicholas Guppy and helped organise trips on the great rivers of the world, to sample their trees, reptiles and wildlife in the company of expert botanists. He also loved a classical ruin (especially when approached by a yacht in the Aegean) and despite his legendary 4th class history degree from Oxford, was impressive when it came to the impromptu translations of Greek and Latin inscriptions. He and Sally travelled across Roman Tunisia to the edge of the Sahara, then took Sally's aunt Clarissa (the stylish Lady Eden) to see Leptis Magna and Cyrene in Libya, then travelled in the Levant alongside Lord Airlie and Lord Salisbury to Palmyra in Syria where they laid flowers on the tomb of the Jane Digby in Damascus, his great-great aunt as the Arab Spring erupted. These Levantine travels included Jordan and Lebanon but Crusader castles were avoided, 'for quite a lot of us have our own castles and are finding them a bit of a burden.' His children delighted in watching their father on holiday re-emerging from the habitual stress of his life, quoting filthy limericks and sunbathing naked on the rocks after lunch like a lizard. Some of the best family holidays were in a rented Greek villa, part of an old mining compound on Euboea (where his great friend Hugo Phillips filled the next door house with his four children) balanced by holidays spent fishing and stalking in a succession of magnificent Highland lodges that he rented for the season, as well as an epic journey to explore the Okavango swamp (when their plane caught fire) and a much cherished riding holiday on a dude ranch in Montana cowboy country. John was knighted twice, built two country houses, was married twice, served as the Chairman of two great British institutions and helped establish two Country Operas. He had worked for the Prince of Wales and was a personal friend of the Queen. It is not a record that is likely to be equalled. It would be his good fortune to die at home in his own bed, watching over the land that he loved and cherished, with Sally holding one hand and Zam the other.

|

Recent Books |