| HOME | About Barnaby | Books | Reviews | Articles | Recommendations | Links | Contact Info |

|

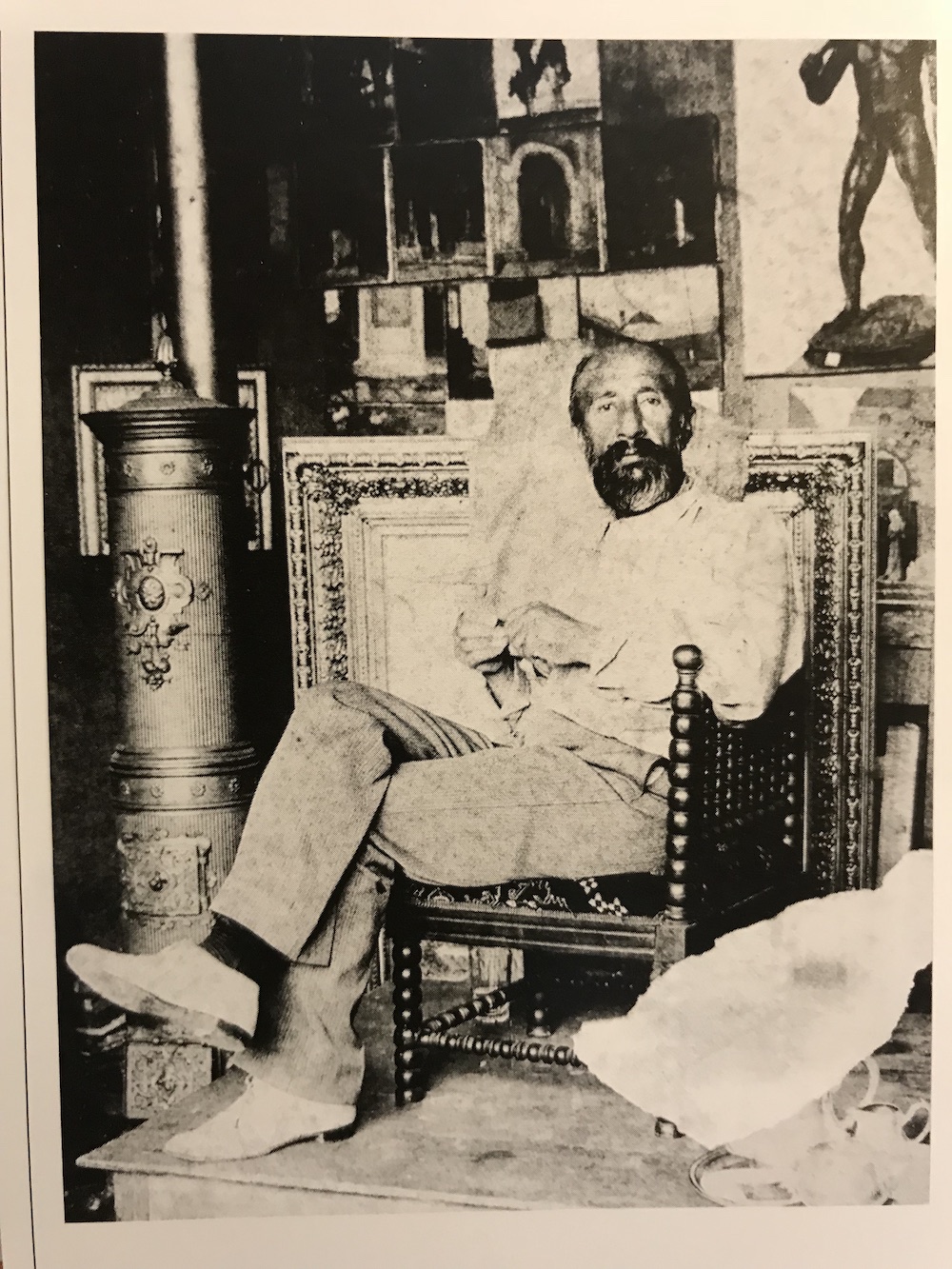

Reading Between the Lines, an article on OSMAN HAMDI BEY, Parisian painter and Ottoman archaeologist Thank God for Osman Hamdi Bey. No serious collection, no important exhibition of Oriental art is complete without a painting by him. The recent auction of his The Tortoise Trainer set new records in Turkey for a native painter. Two very determined institutions drove the price sky high. In his life and in his work, in his family and in his decency, in his faith and in his politics, in his humour and in his paintings this artist proves a happy corrective to the vast accumulation of occidental self-hatred that has piled up in confusing knots around the subject of Orientalist art. Without over-simplifying things, there has been a dangerous wholesale acceptance of Edward Said’s provocative suggestion (in his 1978 book Orientalism) that romanticised images of the Middle East had served to weaken, feminise, titillate and belittle the societies they depicted, and so served as justification for colonial invasion and imperial penetration. In short anyone, who is not a native, but who writes or paints about the Middle East is either a western spy or an ethno-pornographer, probably both.

Not all the painters of the Orientalist school are titillating and belittling. The modern East certainly doesn’t think so, whatever the new British Museum catalogue might tell you in the forthcoming show that opens this October. In “Young Woman Reading” the book that lies open, respectfully wrapped in a linen cloth embroidered in silk, is written in Persian in Arabic script. It is impossible to make a positive identification, other than to say that is not the Koran, but in the scale and shape of the calligraphy it could be a collection of poetic couplets. We know that scrapbooks of different styles of calligraphy were treasured items in any literate household, and might include verses that described the attributes of the Prophet or the Ninety-Nine names of God. Since the language reforms of Ataturk, a young Turkish woman can no longer read such a book. For Turkish is now written in a western script and has been cleansed of the rich fusion of Turkic, Persian and Arabic used in the heyday of the Ottoman Empire. Osman has placed his reader in an institutional environment. It is emphatically not a domestic interior. The dazzling spread of hexagonal tiles, the complex brazen geometric screen, the marble window-frame, the view across cypress trees immediately suggests an Islamic library attached to an imperial tomb within a mosque complex, such as the cluster of foundations that stand in the shadow of the Ayia Sophia and the Blue Mosque in the centre of Istanbul. But this is no casual visit, an incense burner has been lit, an ornate inlaid book stand (mother of pearl squares set into ivory on an ebony frame) has been set up and a carpet has been spread. We are in the presence of someone important with privileged access to the inner courtyards of Ottoman culture. Yet it is also intimate for this is an Ottoman woman, who has taken off her outer coat and the wafer-thin white veils that would otherwise have been worn on all public occasions. We see her in an immaculately tailored kaftan, that plays with the Ottoman love affair with different forms of muted yellow: old gold on white set against stripes of cooked quince-weld yellow with those typically wide, ornate sleeves. You will need to look to the works of Jean-Etienne Liotard (1702-1789) and Fausto Zonaro (1854-1929) to find the same fine eye for the detail of Ottoman tailoring married to respect for the female form. If her dress marks her out as a member of the Ottoman elite, her literacy is no longer such an indication. The mandatory elementary education act of 1869 was already eight years old and had produced a vast demand for female teachers in the chief cities of the Ottoman Empire. But Young Woman Reading has nothing of the school room about it, it is marked by the silence and leisure of a planned visit to a library kiosk, with something of a private ritual about it, of solemnity and dignity touched by a search for answers and inspiration. …. Osman Hamdi Bey was born in 1842, one of the sons of Ibrahim Edheim Pasha (1819-1893). His father rose to the very summit of Ottoman society, serving as Ambassador to Berlin and Vienna, Grand Vizier in 1877 and Minister of the Interior from 1883-5. His father’s life reads like the unlikely plot of a play by Shakespeare. Born Greek, he was taken captive as a boy and sold as a slave in Istanbul, having been spared during the massacre of Chios in 1822. He was rescued by a childless Ottoman admiral (Hüsrev Pasha), who bought a number of boys at the slave market, freeing them and educating them to be model members of society. It is claimed that eighty Ottoman officials and officers, all his adopted sons, said their prayers over the admiral’s grave. Ibrahim Edheim was clever enough to be one of the scholars selected to be sent to Paris in 1831. He studied medicine (becoming a friend of Louis Pasteur) before switching to the Ecole des Mines after which he returned home to work. Osman was following a family tradition when he graduated from his law studies in Istanbul, aged 18 and finished his education in Paris. He spent nine years in Paris, gradually shedding the law in order to study at such freelance private art schools as that established by Jean-Leon Gerome´and Gustave Boulanger. There is no documentary confirmation of an enrolment, but Jean-Leon Gerome´ was certainly in his heyday in exactly this period, producing vast canvasses drawn from French history, the Classics and the Orient, as well as experimenting with sculptures in coloured marbles, metals and inlays. He had already travelled several times to the Middle East, was a friend of the Empress Eugene, and having married the daughter of an art-dealer, ran a grand house in Rue Bruxelles where he taught drawing, painting and sculpture. His influence was vast. It is estimated that two thousand students passed through his studio, and his house was known to be the most riotous but also artistically the most rigorous. Osman fell in love with Marie, a fellow student, who he married (with his father’s permission) and returned to Istanbul in 1869. Two years before this he had succeeded in getting three of his canvasses into a Paris exhibition: “Black Sea Soldier”, “Repose of the Gypsies”, “Death of the Soldier” – current whereabouts unknown. But the carefree days of an art student in Paris were over. Osman joined the staff of Midhat Pasha (1822-1883) who had been sent into a form of internal exile, as governor of distant southern Iraq. Midhat Pasha was an exceptional man, the Istanbul-born son of a Muslim cleric who was dedicated to good governance and internal reform. His three years in Baghdad were a uniquely positive period of Ottoman governance, during which the province was transformed by the construction of new roads, bridges, new schools and hospitals. It was a dazzling illustration of what could be done by one man with energy, working within the long-established traditions of Islamic charitable foundations. There is a souvenir of Osman’s time in the Baghdad, for “The Mosque” has been dated to 1869. By 1871 Osman was back in Istanbul working in the protocol department of the Sultan’s Palace. Ten years later, the death of the first director of the fledgling national archaeological collection (the German scholar Dr Philip Anton Detheir) left a vacancy. Osman was selected for the post. Alexander Vallaumy (a student friend from Paris who was also an Istanbul-born Levantine, the son of a pastry chef) was promptly commissioned to build the handsome Archaeological Museum which still stands in the lower gardens of the Topkapi Palace. It was a good site, that acknowledged the centuries-old role of the palace as both a store house of treasures and a teaching school. Some of Vallaumy’s other projects: the Pera Palace Hotel and the Imperial Ottoman Bank have also well stood the test of time. Two years later (in 1882) Osman Hamdi Bey established the first Ottoman Academy of Fine Arts. It stood directly opposite the new museum (the better to make use of its artistic treasures) in the building that now houses the artefacts of the Museum of the Ancient East. Osman knew exactly what was needed. A staff of eight lecturers selected just twenty students a year, using a foundation year to establish their future specialisations; either in painting, sculpture or engraving. This Academy has grown over the years, and is now a free-standing university - the Mimar Sinan - which overlooks the Bosphorus. Two years later Hamdi Bey drew up the first law against smuggling antiquities out of the Ottoman Empire, and established working partnerships with foreign universities (such as the University of Pennsylvania) to permit excavations which would help to train the first generation of Ottoman archaeologists. Osman personally directed three pioneering excavations: an investigation into the mountain top temple-shrine of Nemrut Dagi (built by the Hellenistic Commagene dynasty), the classical Temple of Hecate at Stratonicea/Lagina deep in the Carian mountains, and the discovery of the so-called Alexander Sarcophagus in Sidon, Lebanon, in 1887. The carvings of Greeks and Persians, and Greeks in Persian dress, some of them still bearing their original colours, on the tomb of the gardener-king Abdalonymus are one of the wonders of the world. Like “Young Woman Reading” which had been finished in 1880, it could confidently exist in two separate cultures without betraying either. FACT BOX Osman Hamdi Bey’s work can be seen in a number of public collections. The Berlin National Gallery has The Persian Carpet Dealer, the Musee d’Orsay in Paris has, Man before a Tomb, and the Penn Museum has both At the Mosque Door and Excavations at Nippur. The latter was a gift from Osman Hamdi Bey, the former was bought as a partial apology to Osman Hamdi Bey for the arrogance of the University of Pennyslvania who had assumed that the objects conserved by Osman Hamdi Bey in the Ottoman Archaeological Museum were for sale. The Pera Museum owns both The Tortoise Trainer and Two Musician Girls and the Turkish Modern Art Museum has mounted exhibitions. The Hamdi Bey Museum occupies the house that he might have used during the summer excavation season in the town of Gebze, which is decorated with copies. They own no original works. Osman Hamdi Bey was born in Istanbul on 30th December 1842 and died there on 24 February 1909. His father had no interest in tracing his Greek ancestry, so by the time Osman took a historical interest in it the trail was cold. There was some suggestion that they were a branch of the Chiot Scaramanga family, who traded in Russia. A branch of this clan became landowners in Sussex, sending their sons to Eton at the same time as Ian Fleming. Osman’s first French wife, Marie, gave birth to two daughters: Fatma and Hayriye. After her death he married a second French Marie (whom he met in Vienna) with whom he would have three more daughters: Melek, Leyla, Nazli (who would marry an Ottoman diplomat) and a son, Edheim.

|

Recent Books

by Barnaby Rogerson    |