| HOME | About Barnaby | Books | Reviews | Articles | Recommendations | Links | Contact Info |

|

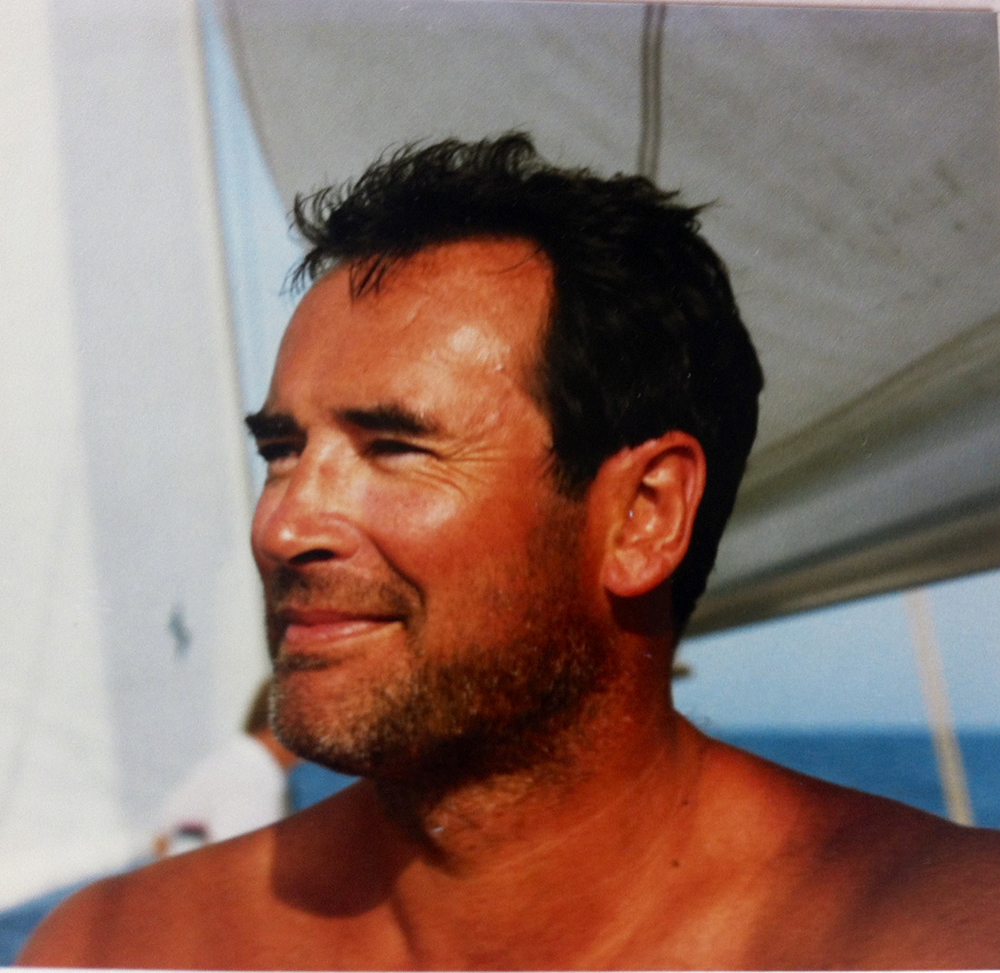

Memorial address for Nico Rogerson, 1943-2017

Nico was always active, as close to Peter Pan as any mortal I have met. He lived life to the full, wonderfully alive to the moment, and for-ever charmed by the prospect of the next adventure. He was highly intelligent but not the least bit interested in matters of the soul or the spirit, in self-examination or introspection. He was fascinated and generous with this life but profoundly indifferent to any promise of the next. As he whispered to my brother just two days before he died, "Game Over". As all the world knows, just four years after leaving university, in 1969, he set up Dewe-Rogerson with Roddy Dewe. They directed the financial P.R. campaign which sold off British Gas (the "tell Sid" campaign with its skillful perception of scarcity and profit embedded into the script) so successfully, that they later advised the government on the sale of Britoil, TSB, BP, British Steel and the water and electricity monopolies.

By 1988 Dewe-Rogerson were turning over 70 million pounds worth of business, employing 400 of the best and brightest. Nico established branches in New York, Central Europe and the Far East to create a worldwide brand which in 1998 was sold for 27 million pounds. He stayed on for a year to oversee the merger with Citigate, after which he devoted his talents to enjoying life while setting up "Concept to Profit", which advised innovative start-ups such as AIGIS Blast Protection. The thing I admired about him most, was his absolute loyalty to his old friends, especially when they were in need. As well as knowing many of the most exalted people across the globe he also had an infectious delight in a rogue and a lygger, a chancer out of luck but still showing some pluck. He had an inspiring delight in the diversity of mankind, with a keen eye for spotting style and self-confidence. The core group of friends was the "ice-cream set" who found each other at Cambridge in 1962 which included David Enderman, Andrew Rayner and David Tonge. It was very difficult for any foreigner to feel welcomed by an Englishman at that time (and probably still is). So if you talk to Renji Sathiah – a Malay diplomat, or Farid Khoury – a Lebanese lawyer, or George Hyatt from Palestine, or such Persians as Khosrow Shahabi and Parvis Khozeimeh-Alam ( now living in Venezuela and enduring his 3rd revolution) or Boulas Sara still trading out of Damascus or the Chilean Sebastian Santa Cruz they can tell you how truly exceptional Nico was as a young man. He was not only untouched by any racial prejudice, but delighted in getting to know their family stories, their culture and style. Nor was Nico some earnest young man on the fringes of the Foreign Office out to forge useful local contacts. These were real friendships, full of laughter and shared misadventures, young men drawn together by the intoxicating fun of gambling, nightclubs and the lure of the perfect lunch. Nico's success with women was legendary, and his friendship with Chantal from Belgium vastly improved his French, just as his German was upgraded by Christina from Strasbourg and Sandra from Vogue sharpened his eye. He had become proficient in many languages (and the ways of the world) by working as a tour guide on Thompson coach tours round Europe during his year off, of which he had many an indecent tale. After graduating in Law from Cambridge in 1965 Nico worked for the Financial Times. This was the time when he got to know the Elliot family. George, Ian and Alan who was already emerging as something big in the city, but kept things lively by running an illegal chemin-de-fer table in Belgrave Square. An e-mail sent by Andrew Rayner gives us a taste of this era: After a week's skinful of vino de Jerez celebrating the autumn sherry harvest-home, the Vendimia, we climbed into my tiny Piper and flew off across Andalucia, on the way buzzing Fermin Bohorquez's bull ranch, Nico hanging out to drop a beach ball inscribed in lipstick in on his bullring where we had the day before been fighting his young bulls at a tienta. We flew up the rock wall of Arcos De La Frontera to surprise friends with a house right on the edge. A day or two with friends in Malaga, then, filing a flight plan to Morocco as one had to in those days of Spanish blockade, we headed for Gibraltar, landing on that remarkable runway across the isthmus and the only road into the Rock, with sea at both ends. I don't think either of us was anywhere sober till after we arrived in Rabat, a full week after leaving Jerez and the entertainments of the generous Domecq family. Yet all this time Nico was a relaxed conspirator, somehow trusting in fate to preserve him from the mistreatment of a sherry sodden pilot, laughing all the while and taking the controls from time to time. A few days thereafter we picked up Renji , an old Cambridge friend, now a third secretary at the Malaysian embassy in Morocco, and his girlfriend to fly through the High Atlas mountains to the desert. All was well until we tried to take off from Ouarzazate to fly back to Marrakesh, forgetting that the high and thin Saharan air didn't hold little aeroplanes up as well as conditions at sea level. By this stage we were also a bit overloaded with women. By heaving on the flaps we got off the ground in time to avoid the valley at the end of the sand runway, then bounced off dunes for a kilometer or two before staggering into the air. As an impressionable teenager I remember the drawing room at St Loo Avenue strewn with invitation cards. There was a series of erotic Beardsley prints hung in the corridor mixed-in with a series about a Regency Buck flirting and gambling and trying to escape his creditors. One learned early on to take the evenings as they unfolded. On one occasion, I watched as Nico's redoubtable old mother was given last minute instructions to act as a host for a drinks party they were throwing, because that highly desirable couple Mr and Mrs Nico Rogerson had decided to go elsewhere. But in the mornings, Nico was always uncle in charge, double checking our flights as he cooked a dawn breakfast, and always driving us himself ( very fast, very skilfully, knowing the hourly shifts in London Traffic flow better than any cabbie) and using the time in the car to have that proper talk. This became the accepted pattern of our relationship, as decades of Rogerson marriages, funerals and celebrations threw us together for a mission, assisted by hampers and checking out restaurants en route. Nico was even closer to my younger brother James, who is a mirror image of his uncle in his passion for skiing, shooting, life in the fast lane and business acumen. Over a memorably liquid 24 hour train journey to meet James in the Alps I had the time to question him about his lonely childhood. Nico was born in the middle of the war and he and his young mother had to take refuge with a whole clan of Rogerson's also sheltering in Red Court. He was brought up in Reed Hall, Royston, Hertfordshire. His father Hugh Rogerson was a distant and authoritarian figure, who had by that time served in two world wars. He had been wounded in a gun turret as a young midshipman at the battle of Jutland, and was obsessed with horses, hounds, hunting and racing. Commander Rogerson preferred the company of his eldest son Barry, who was not only a successful amateur jockey but worked beside him at Harrington & Page. Nico remembered this old family malting business with bemused affection, which included a foundation stone that had been laid by his great grandfather Josiah. The head clerk wore a frock coat, and wrote out bills with a steel nib at a standing desk. Great brick kilns lined with horse-hair were fired up with bundles of coppiced hornbeam in which teams of young workers, all dressed alike in caps, cotton trousers tied with string and canvas boots turned the malt over with wide ash-wood shovels. Old men were given the simpler task of filling and sewing up the hessian sacks by hand or snoozing away the afternoon. For there was a flowing ‘tap' on hand from the brewery to cool down the workers whose shifts starting at dawn, and worked on into the night in the season, which lasted in September and halted with the last frost. Business was either done in the saddle, meeting farmers on their own land out hunting, or at the table, wining and dining the Brewers of London and East Anglia. In this environment Nico forged a very close bond with his mother Olivia Worthington, while his boarding schools ( Cheam followed by Winchester) were more of a liberation than a tribulation, and according to Nico were chosen by his father due to their proximity to the Newbury racecourse. In the holidays Olivia had the good sense to take him on holidays to the bustling households of his endlessly hospitable Rogerson uncles, either Cottesmore with its own grass tennis courts and golf course, animated by his playmate cousins Mark and Mary-Lou while his uncle John included him in the shoots at Sussex and Norfolk. Whenever I questioned Nico about his father, I noticed how he first instinctively checked that his shoes were polished and his finger nails were clean before answering. But now they are both gone, I see that their characters were not so dissimilar. Nico certainly shared with his father a lifelong horror of a stained shirt and of being late, and a delight in fast cars, women and dogs. I feel myself lucky to have known, and loved the very different characters of all three of my aunts: Elizabeth Rummel, Caroline Le Bas and Dinah Verry. Nico blamed himself for the break-up of his first marriage especially which happened during the years he spent building up the international division of Dewe-Rogerson. In their heyday, they were a beautiful couple, and Elizabeth remained a model, who also dabbled in fashion and design. Nico was a loving and generous step-father to Elizabeth's two sons, Michael and Sandy who would both add Rogerson to their Polish surname. He entered their life, aged 8 and 11 on Christmas day in 1972 and were immediately enchanted by this man who took them for a drive in his open-top Porsche in a leather jacket, singing as he drove at incredible speeds. Caroline Le Bas ran her own PR company which worked with Dewe-Rogerson but that never got in the way of her passionate commitment to the Labour party which she shared with her father, Lord Gilbert. She would later use her skills to develop Philip Gould's focus groups, with which Tony Blair seized control of the middle ground of politics. It was Caroline's passion for sailing that took them across the Pacific and first brought Nico to the Isle of Wight, initially renting a simple terraced house (no 2 Coastguard cottage) in Yarmouth before they found a house that overlooked the Newtown creek. Her early death nearly felled the otherwise unquenchable optimism of Nico. But very fortunately, his saviour was at hand. Dinah was as clever and as good as cook as he was (and had also survived the death of the love of her life) and came from a much better family than the Rogersons, but one that had already become implicated with this clan, for Dinah's sporting uncle Tim Nicolson had married Nico's cousin, Valda Rogerson. Together they bought the Old Parsonage to its glittering heyday, constantly being enlarged and improved through Dinah's skills as a decorator and love of an improving project. As we have all experienced, they turned it into a place of legendary and abundant hospitality for the last fifteen years - which rightly now seems a whole lifetime together. Nico effortlessly became a co-conspirator to Dinah's mother Viv (the only woman I have met who in wit and force of character equalled his own mother Olivia) and became not so much a step-father but a friend and trusted mentor to Dicken, Georgia and Felix. He had no grandchildren to call his own, but he was a genuinely loving witness at the emerging characters of the next generation, that were an unexpected enchantment blossoming out of his generosity as uncle and step-father. To celebrate his 70th birthday, representatives of Nico's various families, be they called Rogerson, Verry, Fiennes or Elliot, sailed up the Nile together on the Khedive's magnificent old dahabiyah. We were heavily outnumbered by the crew, who tried to treat us with kid gloves, but I watched as Nico quietly took the Major-Domo aside and told him he was not asking 'whether' it was safe for us to swim in the Nile – but 'where' and as an ice-breaker got his squad to challenge the crew to a football match on the first sandbank. I am, like most of this congregation, locked into an unredeemable debt of hospitality to Nico and Dinah for umpteen meals, weekends, holidays and shared adventures. But all of us are also in Dinah's debt for the loving care with which she looked after Nico to the very, very last in the way that he wanted. He was not exactly secretive about his illness, just not interested in false emotions. "This above all: to thine own self be true, And it must follow, as the night the day, Thou canst not then be false to any man."

|

Recent Books

by Barnaby Rogerson    |

Nico was a card-player, a risk-taker, a brilliant shot, a passionate fisherman, an inspired cook and an attentive host. He had a quick wit but one that was tempered by his natural charm and kindness. I cannot recall an unkind, an angry or a cross word - though he had eloquent eyes and hand gestures with which he could deliver a silent judgement.

Nico was a card-player, a risk-taker, a brilliant shot, a passionate fisherman, an inspired cook and an attentive host. He had a quick wit but one that was tempered by his natural charm and kindness. I cannot recall an unkind, an angry or a cross word - though he had eloquent eyes and hand gestures with which he could deliver a silent judgement.

Dewe-Rogerson spearheaded the Thatcherite revolution, delivered leaner, more efficient government and helped create the post-socialist world order which we live in today, even if the initial promise of a new share-owning democracy did not emerge.

Dewe-Rogerson spearheaded the Thatcherite revolution, delivered leaner, more efficient government and helped create the post-socialist world order which we live in today, even if the initial promise of a new share-owning democracy did not emerge.